Reality check

Poverty, inequality and exclusion are key factors contributing to the devastating effects of COVID-19 on all African countries. Issues like fragile healthcare systems, food insecurity and large informal economies make this much more than a massive health and economic crisis. COVID-19 is a fundamental development crisis for Africa.

A recent McKinsey report highlights the extensive impact of COVID-19 on Africa’s economies – noting the slowdown in economic growth, job and productivity losses, and bankruptcies. Importantly, the analysis also notes that school and university closures will impact future human resource capacity and are likely to particularly impact girls, some who may not return to school.

The interaction between gender and the pandemic is particularly important in Africa. In many countries the majority of healthcare workers (nurses) are women, and women are also primary care providers at home.[1] Informal traders and especially informal cross-border traders are predominantly women. Women’s roles in agriculture vary across countries; in some, for example Uganda, Tanzania and Malawi, women’s labour input into crop production is higher than 50%.

World Health Organisation (WHO) Regional Director for Africa Dr. Mathsidiso Moeti has noted, “for socially restrictive measures to be effective, they must be accompanied by strong, sustained and targeted public health measures that locate, isolate, test and treat COVID-19 cases.” Nationwide lockdowns have been implemented in a number of African countries, including Kenya, Uganda, the Republic of the Congo, Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

South Africa’s initial stringent lockdown regulations were eased when it became apparent that a complete lockdown was not feasible. Social distancing, lockdowns and recommendations to frequently wash hands mean very little when your household does not have access to running water. Compound this with living with members of your extended family in a small corrugated iron shack, and you are all dependent on the income that your mother generates through cross-border trade.

Lockdowns, social distancing and other measures, that include trade restrictions, aimed at reducing the transmission of the virus also mean loss of income and jobs, as well as closure of small and vulnerable businesses. Making trade easier and less costly with due safety measures should be a key policy objective.

The pernicious effect of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) on intra-Africa trade far exceeds that of tariff barriers. Policy makers should not add unnecessary NTBs during the crisis, and COVID-19 should push us to look to digital solutions to reduce the transaction costs of trade.

COVID-19 and intra-Africa trade

Intra-Africa trade remains low by comparison with other regions. Africa’s exports are predominantly commodities like oil, minerals, cocoa and coffee, so it can be expected that for the foreseeable future Africa will continue to trade mostly with global trading partners. Growth slowdowns across the world will mean lower export earnings.

In 2018, 15% of Africa’s total exports were destined for other African countries. South Africa is a key driver of intra-Africa exports, accounting for 34% of the total intra-Africa exports. South Africa’s distribution industries (logistics, freight forwarding, wholesale and retail) are important conduits for its exports of agricultural and industrial goods, especially in east and southern Africa. Approximately two-thirds of intra-Africa trade takes place in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and about half within the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).[2]

At this time, South Africa’s deep integration into southern Africa especially makes the region very vulnerable to any trade measures adopted by the country. Delays at borders and export restrictions[3] will impact vital supply chains across this region and exacerbate the COVID-19 impact on fragile neighbouring economies. A second-round effect could well be a new wave of migration to South Africa, as those left destitute seek income opportunities elsewhere.

Informal cross-border trade

Estimates of intra-Africa trade generally do not include informal cross-border trade (ICBT).

Studies across the continent indicate that ICBT is substantial and that it includes both agricultural as well as industrial goods.

ICBT is rarely illegal. Lack of formal employment opportunities in most African countries make informal economic activities the only viable income-generating opportunities. Tariffs, complex rules of origin and other NTBs associated with customs procedures make ICBT the preferred trade option. Time required to comply with procedures is also a major factor for informal traders. Lack of access to credit means that traders have to make regular trips across a border – weekly or even daily – to ensure reliable household income. For customers, ICBT has during food crises often been more reliable than official food support.

Since 2005, the Uganda Bureau of Statistics and the Bank of Uganda have been doing surveys of ICBT with east African neighbours. The 2016 study concludes that ICBT accounts for between 25-40% of formal intra-regional trade flows. In SADC, ICBT is also significant, accounting for between 30-40% of total intra-SADC trade, with an estimated value of US$17.6 billion. Women make up the largest share of informal traders; more than half in western and central Africa and about 70% in southern Africa, according to the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO). Unsurprisingly, there is increasing evidence that ICBT plays an important role in food security and poverty alleviation.

ICBT includes agricultural goods (staples such as maize, rice, soybeans) as well as industrial goods (shoes, clothes). Some regional economic communities, e.g. the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA), have introduced Simplified Trade Regimes (STR) for small traders, while others like SADC have not.

COVID-19 is a good reason to adopt STRs in regional economic communities where they don't exist yet, and to review and improve the regimes that do exist.

Trade policy responses to COVID-19

Protectionist policies at the best of times and most certainly during times of crisis are not advisable. The reality is that if all adopt such beggar-thy-neighbour policies, we will all lose. This will only serve to deepen the crisis and make recovery more difficult and costly. With unrestricted trade, goods can move from where there is a surplus to where there is a deficit. This is necessary not only for medical equipment, medicines and personal protective equipment but also for all other goods. Agricultural trade is of course particularly important, especially for food insecure households in Africa.

The World Bank has published a list of trade policy do’s and don'ts in response to COVID-19. The do’s include measures to facilitate trade by reducing tariffs to zero on COVID-related medical products and food products, and removing quantitative restrictions and export taxes. The don’ts include trade restrictions to protect domestic industry and closing borders. Indications are, however, that most African countries are implementing measures that will impact trade – including export restrictions for specific products and other border measures that will slow trade and reduce supply chain efficiency.

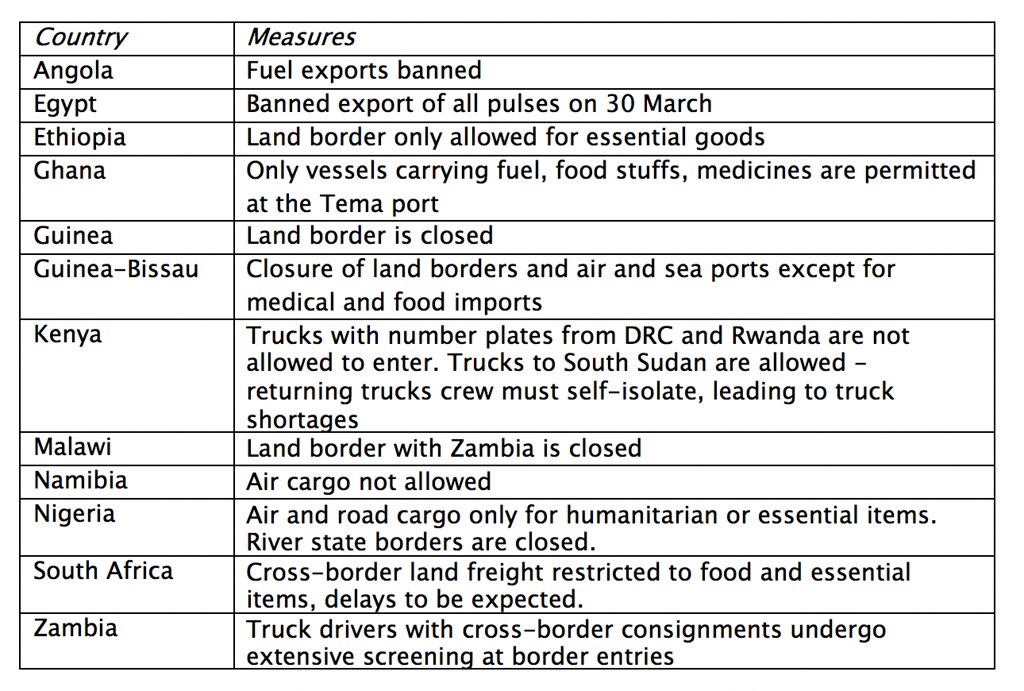

Below is a selection of airport, border and port measures that some African countries have introduced (as at 3 April 2020).

Source: https://logcluster.org/document/global-logistics-cluster-covid-19-cargo…

These restrictions apply to trade in goods, but also impact transport, logistics and other services. This is a reminder that the impact of trade restrictions will permeate throughout the economy. We can expect that adjustment costs after the crisis for developing and especially for least developed countries (LDCs) will be markedly higher than for developed countries. The fact that Africa is home to 33 of the world's 47 LDCs makes the continent particularly vulnerable both now and post-crisis. This makes it even more important for African countries to be cautious when considering restrictive trade measures.

-----------------------------

[1] Burkina Faso, Burundi, Egypt, Eswatini, Ghana, Nigeria, Mozambique and Kenya are among the African countries where the majority of nurses are women.

[2] All SACU member states (South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Eswatini) also belong to SADC.

[3] As of 20 March, 2020 export of face masks, disinfectants, alcohol-based sanitisers and hydroxychloroquine, require export permits, see details - http://www.itac.org.za/upload/Covid-19%20Export%20Control%20Reg%2027%20March%202020.pdf. South Africa has also introduced rebates (subject to a permit) on imports of essential products – these include food preparations, medicines and medical supplies, for details, see http://www.itac.org.za/upload/Rebate%20Application%20(COVID-19).pdf

------------------

Trudi Hartzenberg is Executive Director of the Trade Law Centre (tralac).

Header image - ©iboy_daniel from Flickr under Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.