International Food Policy Research Institute (IFRPRI) Senior Research Fellow discusses the challenges and opportunities for food security in least developed countries amidst the COVID-19 pandemic

According to your Food Export Restrictions Tracker, it seems that currently 18 countries have implemented food export restrictions linked to COVID-19, representing just over 5.8% of global calorie markets. What does that mean for global food security?

Globally, we don’t have a major shutdown of markets mainly because all the big exporters have not limited their food exports. However, some countries and some regions are at risk because their major suppliers are limiting their exports.

The wheat market is mainly being impacted by export restrictions implemented by the Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan and the rice market is being impacted by Vietnam’s export restrictions. So if we look at Egypt for example, which gets 46% of its staple calories from the Ukraine and Russia, these restrictions are having a significant impact. This is the same for Ghana, which imports half of its rice from Vietnam.

How are LDCs currently faring, particularly those that depend on imports of rice and wheat?

We estimate that roughly 16-18% of basic food products that were imported by LDCs prior to COVID-19 are now at risk due to current export restrictions.

When it comes to the LDCs most greatly impacted, Afghanistan is in a tricky situation. Half of their wheat products normally come from Kazakhstan and they are a landlocked country so they are quite vulnerable at the moment.

In Africa, the main commodity that they are sourcing from outside the continent is rice. Much of rural Africa relies mainly on local production of cassava and white maize and so they are not particularly impacted by what is happening in global calorie markets. However, rice is quite important in urban centers and the disruption in its availability is a big problem for urban populations.

The main trouble in international trade is that countries putting in place export restrictions are not taking into account the impact of these decisions on LDCs, which may be thousands of kilometres away.

COVID-19 is also posing a threat to domestic trade of food in LDCs. In some countries, a lack of coordination between the public and private sector has meant lockdown measures have been announced and markets closed without allowing enough time to transport sufficient food into the cities. So poor populations in urban centers are not only suffering from the lack of availability of imported food, but also a disruption in availability of food from within their own country.

While these limitations on movement of goods and people make sense from a health perspective, we are starting to see that some measures are being implemented in excessive ways, particularly in LDCs where there is a high level of informality. Informal traders are the lifeblood of many African cities, and they are being picked up by police for being outside.

What have you been noticing about how LDCs are responding to the export bans as well as the domestic trade challenges? What measures have they taken to curb the effects?

Many LDCs are trying to implement social safety nets to provide income to their poor population. Some have also tried to find a way to support SMEs through tax exemptions, better financing and helping farmers secure inputs. One of the challenges is to get the fiscal capacity to pay for these measures, which is why debt relief or at least a moratorium on debt payment will be very important in the years to come.

The main trouble in international trade is that countries putting in place export restrictions are not taking into account the impact of these decisions on LDCs, which may be thousands of kilometres away.

However, while LDCs can be victim of the restrictions, they also do not hesitate to implement them. Formally, we have not recorded any LDCs implementing export restrictions but informally I have received a lot of testimonies stating that this is happening. For example, Burkina Faso has blocked grain and seed exports to Niger. Here you have two landlocked countries that are part of the same trading bloc, but then you see this protectionist gut reaction that will be detrimental to its neighboring LDC that it should be cooperating with.

What would a good policy response to the current situation look like?

The first thing is to really avoid implementing export restrictions. The good news is that the current export restrictions are much smaller than those that were implemented in the 2007/2008 crisis.

Do you that’s because countries have learned from that crisis?

I think so. In 2007/2008, India blocked a lot of export that would have actually been a good commercial and diplomatic move for them, and a lot of grain was wasted because there was no storage capacity. So they wasted a lot of money, hurt their farmers, hurt their traders, hurt their neighbours, and in the end hurt their taxpayers.

There is also more monitoring now. A group called AMIS – Agricultural Market Information System – coordinated by the WTO, OECD, FAO and a number of international organisations, provide information and predictions to markets and policymakers about the level of stocks and also monitor these policy changes. So countries today cannot have the kind of murky behaviour they may have had 10 years ago as other countries will hold you accountable.

Coming back to your initial question about a good policy response, implementing social safety nets particularly targeting urban populations and women is quite important.

Why is it important to target women?

In most LDCs, the woman of the family will prepare the food and go to the market to find food. So providing social safety nets to the woman of the family means the money is going to be used for this daily food expenditure. And at the same time, women can also be the main victim when there is food insecurity, in the sense that both adult women and young women are the first to cut their food consumption within a household.

It’s also important to think about shocks. Locust infestations, droughts and floods that destroy your local production will always be there so you need to have balance and diversification. To think that your food security can be based on local supply only is as risky as thinking you should just rely on one exporter for your food.

A lot of women are also informal workers without a lot of education, so they are not going to work remotely, they don’t have a lot of assets that can help them absorb economic shocks, and they are heavily involved in low skill, face-to-face services that are being totally disrupted by COVID-19. So now even their main source of income, in many cases, is directly hurt by the crisis.

What needs to happen to overcome domestic trade issues?

Trade facilitation needs to be implemented. Due to social distancing, we cannot do paperwork or inspections, so people need to start to move to electronic certification or accept electronic documents. This is particularly important for domestic trade, as we don’t want to create a system where it would be easier for an international trader than a domestic trader to get paperwork done.

Next, the way social distancing or lockdown is announced is important. In some countries, decisions have been within two days which haven’t allowed for the population to prepare. It’s important to ensure that you implement rules that make sense for the private sector.

As an example, a policy that doesn’t allow trucks to carry non-food and food products doesn’t work in East or West Africa, where trucks leave the city carrying non-food products, and carry food products when returning as it doesn’t make any sense for a truck driver to use a truck that is half-filled. This policy basically kills the transportation system that also carries food.

Given that rural communities are able to rely on local production, is increased localization of food part of the answer?

The domestic supply chain is actually just as disrupted as the global supply chain. Right now we are struggling to move food within countries and we have problems processing food. For example, the meat sector in the US is facing difficulties moving local pigs to the slaughterhouse and getting them processed.

There are still challenges in going local. In order to grow crops you still need inputs, seeds, fertilizer; not all countries have phosphorous, for example, so you still need trades.

It’s also important to think about shocks. Locust infestations, droughts and floods that destroy your local production will always be there so you need to have balance and diversification. To think that your food security can be based on local supply only is as risky as thinking you should just rely on one exporter for your food.

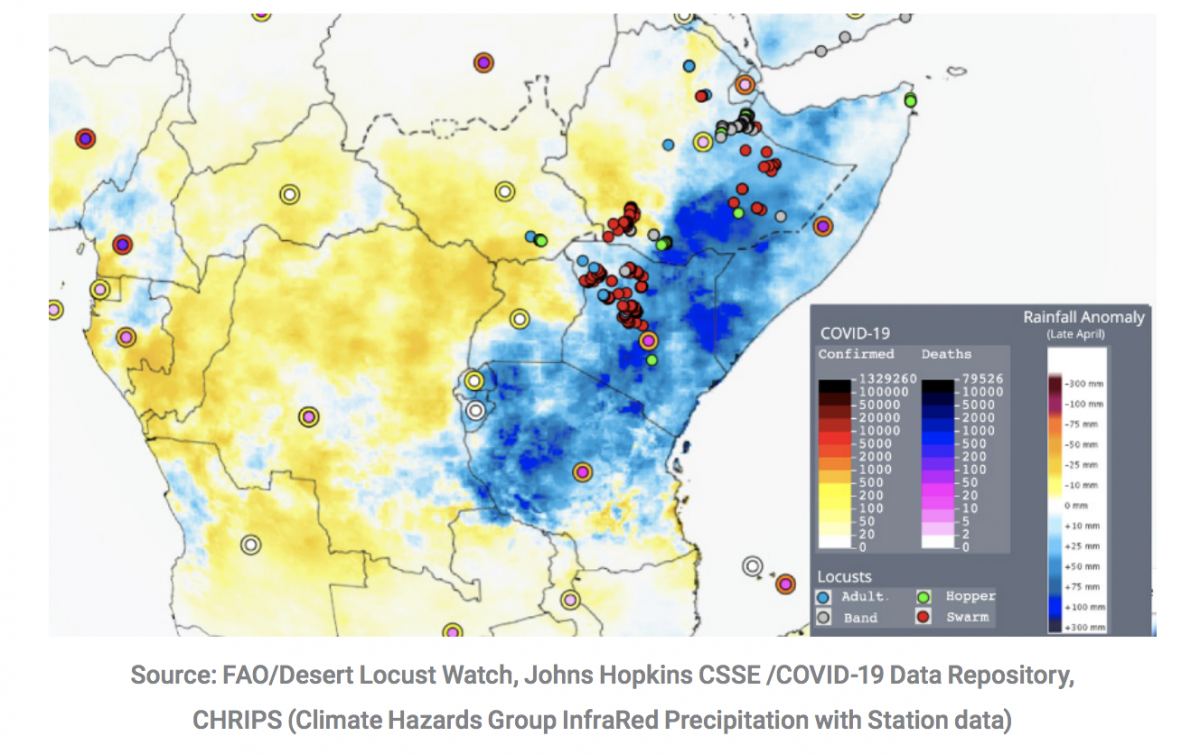

A "triple menace" in East Africa: COVID-19, locusts and heavy rains

Source: Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition, UN 2020

A major risk we are seeing now is that people are thinking that the problem is globalisation or international markets. Even if I take even a very developed economy like Italy, the main problem was moving people from North Italy to Central Italy and South Italy. Policymakers and populations have to go beyond the rhetoric of ‘oh, my border is protecting me…everything within my border is nice and everything outside my border is not’ and look at evidence of the problem to find the proper solution.

What could international organisations be doing right now to help LDCs with food security issues?

Debt relief is a big, serious issue. LDCs are going to need to have fiscal capacity to implement the policies that are needed. And that means they will also have to manage their exchange rate, because their central bank will be under a lot of pressure if they have to pay debt in foreign currency while implementing expansionist monetary policy to support economic activity during the crisis..

If LDCs are to pay for a social safety net, they will need money. And so the IMF, the World Bank and IFI will need to work with them on that.

We also need to promote and share good policies. There are still opportunities for countries to learn from each other and implement the same systems. I think we are at a time where we are seeing a lot of policy innovations taking place, and international organisations can help countries follow and learn from what others are doing.

If the crisis worsens, what’s important for LDC country governments to know?

Keeping the flow of goods, in particular food products, within countries and across countries as undisrupted as possible, is key.

There is also a big question about how LDCs pay for their food import bill, particularly given the major losses in revenue due to the fall in tourism activities, commodity prices and remittances. I think that we will get over the health crisis in the next 3-6 months, but the economic costs of this health crisis are going to carry on for months, if not years. I think that we are going to end the year with a level of public debt, and in some cases private debt, that we have not seen since WWII.

What this means for international solidarity is not clear. How we are going to manage collectively this debt? Is it going to mean that for rich countries we will cut foreign aid, thinking that we need to deal with our own problems at home first? That has serious implications for development.

In every crisis there’s opportunity; with innovative policymaking, could some systems come out better?

If these export restrictions stay under control it will prove that, to some extent, the international community can behave in terms of crisis.

My biggest hope is that we may see in many LDC countries, potentially in Africa, something that will look better than we have seen so far. There have been many things, such as trade facilitation, that were previously considered too hard or too complicated, that are being implemented because now is a time for action. It will be difficult to go back to a world where people say it’s not possible, because we have seen that innovation is possible.

Right now, COVID-19 is a big shock, but it has been largely manageable. We are going to have other crises, and maybe the learning and innovation we do today will stand us in good stead for future crises.

Header image of a kava ceremony in Fiji - ©Africa Renewal via Flickr Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.