Trade for Development news discussed global value chains (GVCs) and least developed countries with Caroline Freund, Director of Trade, Regional Integration and Investment Climate, World Bank Group, and co-Director of the forthcoming World Development Report 2020 on Global Value Chains: Trading for Development.

What motived the World Bank to devote the World Development Report 2020 to GVCs?

It was a recognition that trade issues are looming large in the world economy. The question for developing countries is whether there is still a path to development through trade integration. Increasingly, it looks like that path is through GVCs which were responsible for much of the increase in trade that occurred in the 1990s and early 2000s. The report explores whether a repeat of that experience is possible, in light of changing technologies, deindustrialisation and an uncertain trade policy environment.

Trends in production activities as a share of global GDP (1995-2014)

What strategies should latecomers to development consider to stimulate economic diversification and maximise the opportunities and gains from GVCs?

There are different ways in which countries participate in GVCs. Some participate by selling raw materials or parts to other countries who then incorporate these imports into their production for export. Others import parts and components from abroad to be used in their exports. The big advantage for developing countries from GVCs is that they need not produce an entire product: they can specialise in tasks and produce at scale with high productivity gains.

As with trade more generally, we find that GVCs are determined by country fundamentals: their size, location, labour and capital endowments, and the quality of their institutions such as regulatory environments and the business climate more broadly.

But countries can shape their future in different ways. The report focuses on the following areas. First connectivity, which is important to access inputs and have a larger market to sell to. Connectivity can be improved through tariff reductions and trade facilitation for example. The second is capital. A country can overcome endowment constraints by increasing foreign direct investment, to bring in capital and know-how. And the third is international cooperation. Institutions can be imported, to a certain extent, through trade agreements that lock in reforms. Cooperation also helps solve coordination failures and supports a predictable trade environment. In short, to successfully integrate developing countries need connectivity, capital and cooperation.

Do you discuss the role of industrial policy in this context?

We find that the development gains from joining manufacturing GVCs are especially large. We look at countries from the point when they are integrated into various types of GVCs and analyse the consequences in terms of growth, employment and productivity. The data show that there is a boost to all three indicators, for all types of trade and GVCs, but it is especially strong for entry into simple manufacturing GVCs.

One of things we consider is special economic zones. Many developing countries enquire about them as a strategy to attract manufacturing employment. The report takes a deep dive into their effectiveness and we find that the majority actually fail. When countries get the policies right – around connectivity and infrastructure for example – they can work. But economic zones have to address a market failure and achieve a reasonable level of governance. If the constraints to attracting investment are associated with political uncertainty or macro instability, for example, establishing special economic zones will not solve the underlying issue as they cannot be contained spatially.

The report is developing a novel conceptual framework that looks at the relational dimension of GVCs. What are some of the lessons that this approach delivers?

The approach taken is that it is not countries that trade, but firms. In GVCs there is a relationship between firms since customised parts and components are often required for production. In many cases, relationships are formal, for example, through multinational enterprises and their subsidiaries. In others, there may be long-term contracts.

We find that GVC trade has stronger growth and productivity effects than standard trade, suggesting these relationships are important. But, there are also equity concerns. There is some evidence that lead firms from advanced countries can extract a large and increasing share of the profits in GVCs.

This relational dimension brings to the fore the importance of contracts, different aspects of the business climate and deep trade agreements for more complex GVCs.

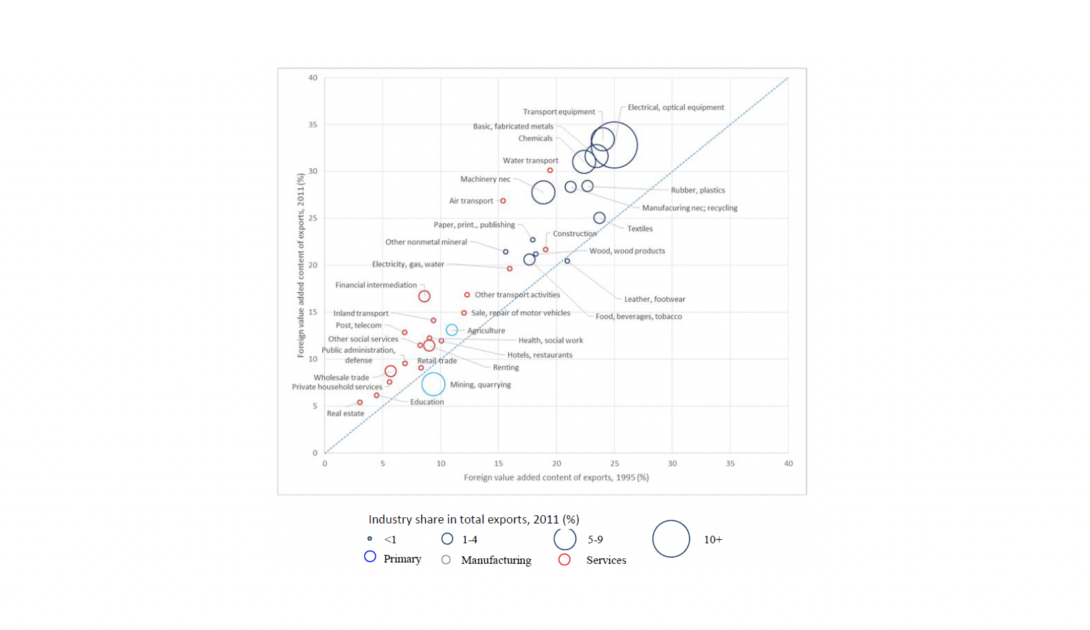

GVCs are playing an increasing role in almost all sectors, especially manufacturing

Note: Industries in which the foreign value-added content has increased are located above the 45-degree line.

The concept note emphasises that “a nontrivial share of low wage developing country exports is in sectors being rapidly automated by their trade partners.” In view of this shift in comparative advantage within a broader pattern of skill-biased technological change, what is the potential for export-led industrialisation and productive employment generation in low wage countries through GVCs?

We are relatively optimistic here. There are different ways in which technology will affect trade. We often think of automation and reductions in trade flows due to production moving closer to home. But technological change also affects trade costs, which continue to decrease, especially with new technologies like artificial intelligence and blockchain. We anticipate more trade because of this trend. In addition, technological change means new products, which will also tend to increase trade in intermediate and final goods.

When we look at technologies like automation and 3D printing there are also two effects. One is that productivity rises because labour is displaced and more production may take place in advanced countries, reducing trade. The other is that rising productivity leads to falling prices, rising demand and more production, so more intermediate inputs and raw materials are needed. This second effect tends to increase trade. The data show that highly automated industries – automotive for example – use more imported parts and components. The pull on trade tends to dominate. We see similar effects in 3D printing – hearing aids for instance – where trade is increasing because any onshoring is outpaced by productivity gains and greater production. We therefore generally anticipate that technology will complement rather than substitute trade.

What about the distributional consequences, between skilled and unskilled labour for example, is that an aspect that you look into?

Yes, the effects on labour are more complicated as workers are displaced. There appears to be a tendency in developed countries, and to a lesser extent in developing countries, towards a higher skill premium. The GVC and technology boom have led to higher growth but they have also had consequences for inequality both within and across countries. As discussed, the mark-ups seem to be accruing more to some firms than others. GVCs tend to cluster activities within countries, resulting in regional disparities. So, GVCs lead to higher growth and less poverty, but in many cases also higher inequality.

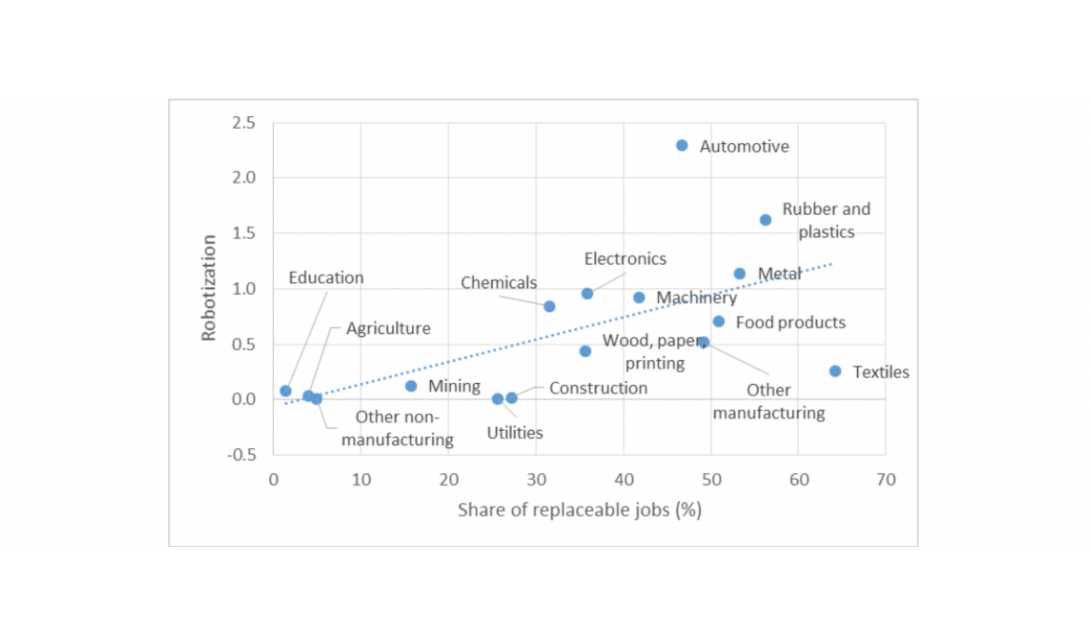

Robot adoption and feasibility of automation across sectors

Indeed, the correlation between economic and social upgrading through GVCs is not automatic. What type of policies are needed to promote social welfare improvements in low income countries?

There are the standard complementary policies for trade that also apply for GVCs. Labour adjustment policies are very important because of the distributional consequences. This means unemployment insurance, for example, as well as active labour market policies that help workers find new jobs. These policies are more affordable in advanced countries. But they are probably also more needed there because of the speed of disruption, due more to technology than trade, towards higher skills. For developing countries, labour mobility is very important because GVCs and growth often tend to be quite concentrated. Workers must be able to move to benefit from opportunities.

On a related note, can you share some of the findings on how participation in GVCs affects female workers in developing countries?

We find that GVCs employ female production workers more intensely than non-GVC manufacturing firms. There is a job creation effect with strong spillovers for low-skilled women and their families. But what we also find is that GVCs do not break the glass ceiling. While women are more likely to be production workers in GVCs than in similar firms, they are also less likely to be owners or managers.

If we turn our attention to the environment, are there areas where GVC-related policies can help tackle some of the urgent challenges that we face?

The transport of goods back and forth is a big concern. Carbon emissions from shipping represent roughly two percent of global emissions and are on the rise. The other concern often raised is the issue of carbon leakage where the most polluting activities migrate to countries with lax regulation. This turns out to be less of an issue because comparative advantage is driven by other factors. And the third concern – possibly the most worrisome – is around waste derived from the increased production and consumption of ever cheaper goods.

Policy considerations that exacerbate these concerns are the under-pricing of fuel and production subsidies. In a world of GVCs, a country that subsidises fuel or an industry will induce effects beyond its borders. The distortion is magnified to some extent.

However, it is important to mention that there are also beneficial environmental effects to GVCs. Consumers and producers have access to more and cheaper environmental goods – for example solar panels. We also see that lead firms tend to push for higher environmental standards in their value chains due to consumer expectations, which is another aspect of the relational dimension. Finally, trade more broadly encourages the world to use resources more efficiently – a case in point being agriculture and trade in embedded water from abundant to scarce countries.

To summarise, there are conflicting environmental effects and our recommendation is that the best way to manage them is by getting the price signal right. A first step would be to remove fuel or production subsidies that incentivise overcapacity and hydrocarbon use. Another would be to tax pollution accordingly so that environmental externalities are priced into the cost of goods. Carbon taxes for example would help reduce emissions from excess production and transport.

What role do you see for international cooperation on trade-related policies and regulation in terms of helping low income countries capture the benefits from participation in GVCs?

International cooperation is critical to ensure an open and predictable trade policy environment. GVCs thrived in the 1990s and early 2000s in part because of low tariffs that were constrained by international commitments in advanced countries and tariff reductions in developing countries. Regional trade agreements also supported the development of especially close regional ties. There is still room for further trade liberalisation in advanced countries, especially in agriculture and processed food, where relatively high tariffs prevent developing countries from entering final stages of production.

The policy response will depend on the type of GVC, which can be divided into three categories: agriculture and resource-based, simple manufacturing and more complex manufacturing. Countries engaged in agriculture and resource-based GVCs tend to have higher trade costs. Improving this situation through integration agreements like the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement and the implementation of trade facilitation measures will help. When moving into the more complex GVCs it becomes important to enter into deeper trade agreements that tackle issues like investment and standards.

One of the newer policy areas the report focuses on is data. Future GVCs might increasingly be around platform firms. Advances in communication technologies and transport enabled the formation of existing GVCs: the next rung is platform firms and the huge amounts of data created. There is a trade-off here between innovation and privacy that needs to be considered, and there are also concerns around competition.

Another important area is tax policy. Because capital has become so easy to move around, and because a large share of profits stem from activities such as R&D and patents, it is much harder to tax firms in GVCs. Cooperation around taxation is essential, not least for developing countries that need the resources to put in place the type of labour adjustment policies discussed earlier.

To end on cooperation, how can aid for trade help equip least developed countries for the GVCs of the future?

The Trade Facilitation Agreement of the World Trade Organization provides some lessons in terms of cooperation and the distribution of gains. Developing countries can implement the agreement at their own pace and support is provided by advanced countries. This is a useful way of dealing with coordination failures that affect GVCs.

The model can be extended into other areas such as standards. Meeting technical barriers to trade or sanitary and phytosanitary standards can be a challenge for developing countries. More assistance in setting up the right bodies, accessing information, acquiring the right technology and getting products certified would help expand participation in value chains.

--------

This policy series has been funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed in this publication are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.