|

|

|

The COVID-19 pandemic has put least developed countries (LDCs) in an extremely precarious position given their limited ability to tackle the unfolding health, economic and humanitarian crises. Despite increasing infection rates, LDCs have yet to experience the worst of the pandemic. As of 25 June 2020, over 240,000 infections and around 4,500 deaths have been reported in the world’s 47 LDCs. The 14 LDCs that are Commonwealth members, and with almost one-third of the total LDC population [1], have almost half of these infections, as well as a similar share of mortalities, making them particularly vulnerable in this pandemic.

However, LDCs confront a trilemma when tackling COVID-19. First, they have poorly resourced and fragile healthcare systems with limited numbers of healthcare professionals. Second, they are net importers of COVID-19-related medical supplies and equipment needed to treat infected persons, even as some major producers restrict these exports. Third, many LDCs are heavily indebted, while lower commodity prices and remittance inflows mean they struggle to finance imports of medical goods at a time of rising prices.

With global demand outstripping supply, LDCs are at the back of the queue when procuring vital medical supplies.

Health-related trade situation

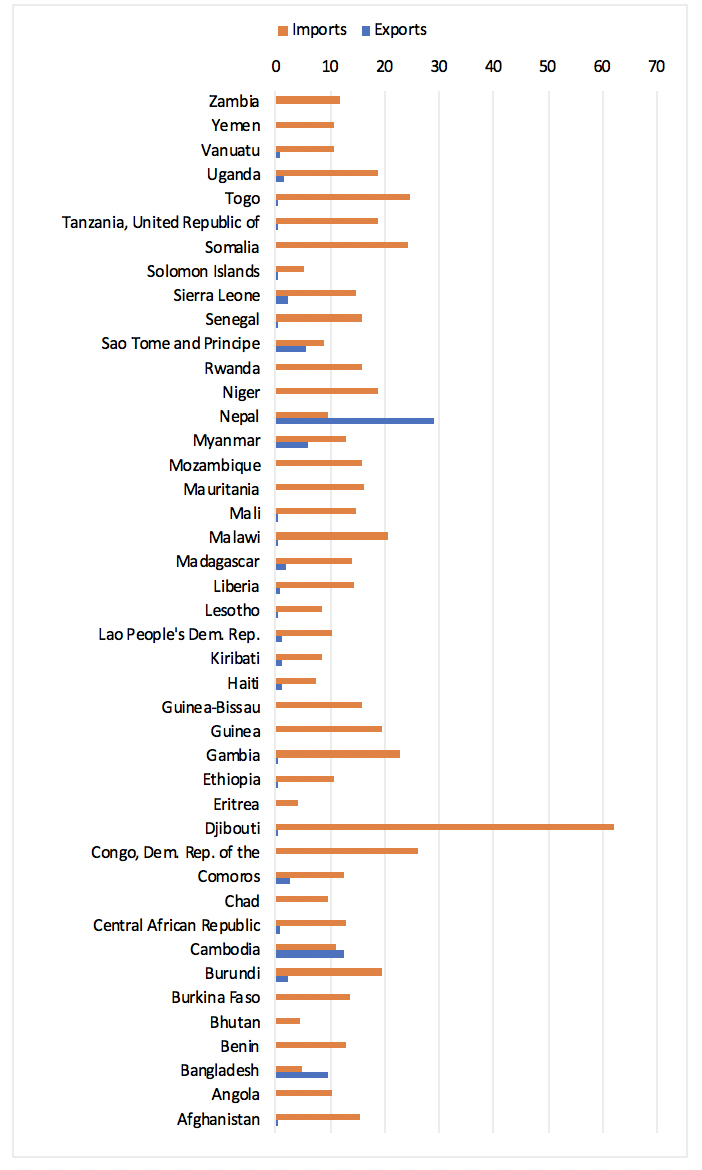

The majority of LDCs depend on international trade and undisrupted supply chains to support an effective health policy response. The share of health-related imports in total merchandise imports varies greatly across LDCs (see Figure 1).[2] Three countries stand out for exports: Nepal (almost three times more than imports), Cambodia and Bangladesh.

Figure 1: Share of COVID-19-related medical goods in LDC merchandise trade (%)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

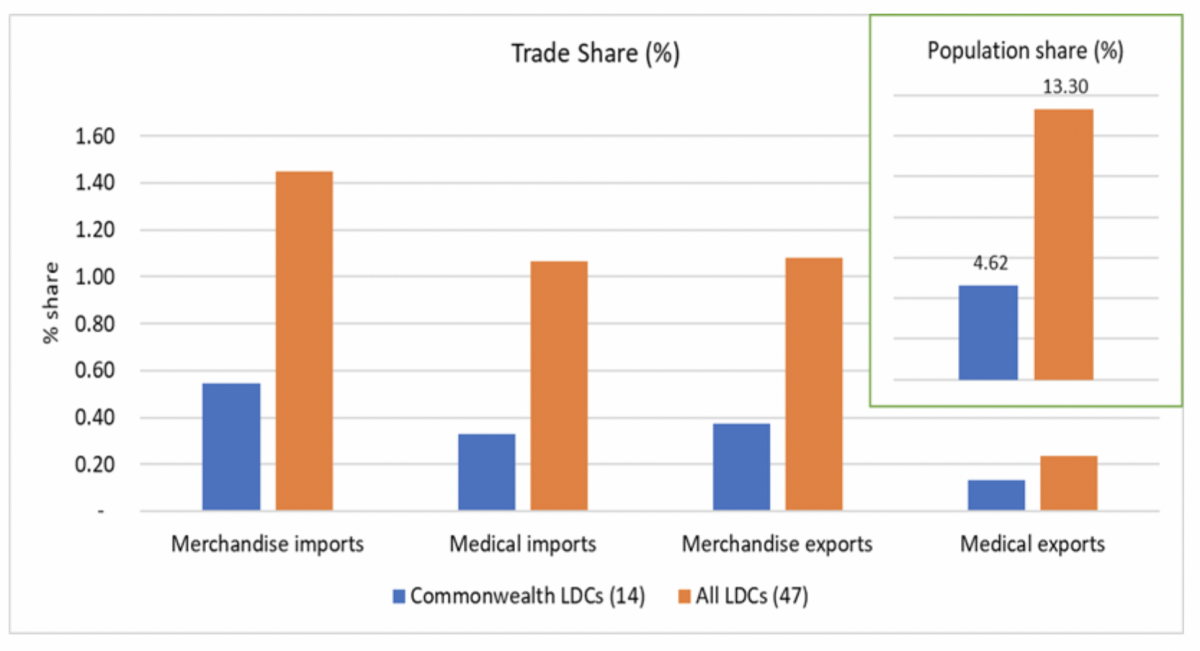

In 2018, global imports of COVID-19-related medical goods were US$695 billion. Of this total, only US$7 billion – or around 1% – was destined for LDCs. This is lower than their share of world merchandise imports (1.45%) as well as world population (13.3%) by a significant margin (Figure 2).

Figure 2: LDCs share in global trade of medical supplies

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS and WDI)

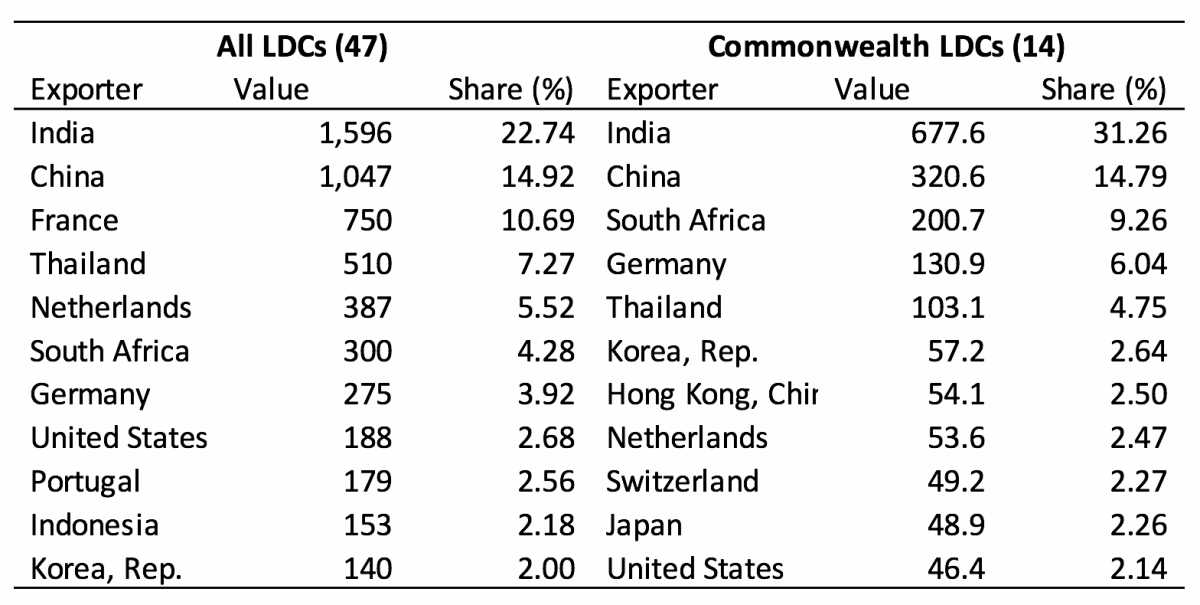

The production and export of COVID-19-related goods is highly concentrated: five countries account for half of the world exports while the top 10 countries account for around 75% (see Table 1). China is the largest producer of personal protective equipment (PPE), whereas the EU and the USA lead in clinical equipment manufacturing. The sources for medical supplies to Commonwealth LDCs are even more concentrated, with India, China, South Africa, Germany and Thailand accounting for two-thirds of all supplies. Because some of these suppliers (India, South Africa) are also grappling with the impact of COVID-19, they are limiting specific exports of medical goods, like PPE.

Table 1: Top 10 sources of COVID-19-related medical supplies to LDCs (US$, Million)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (using data from WITS)

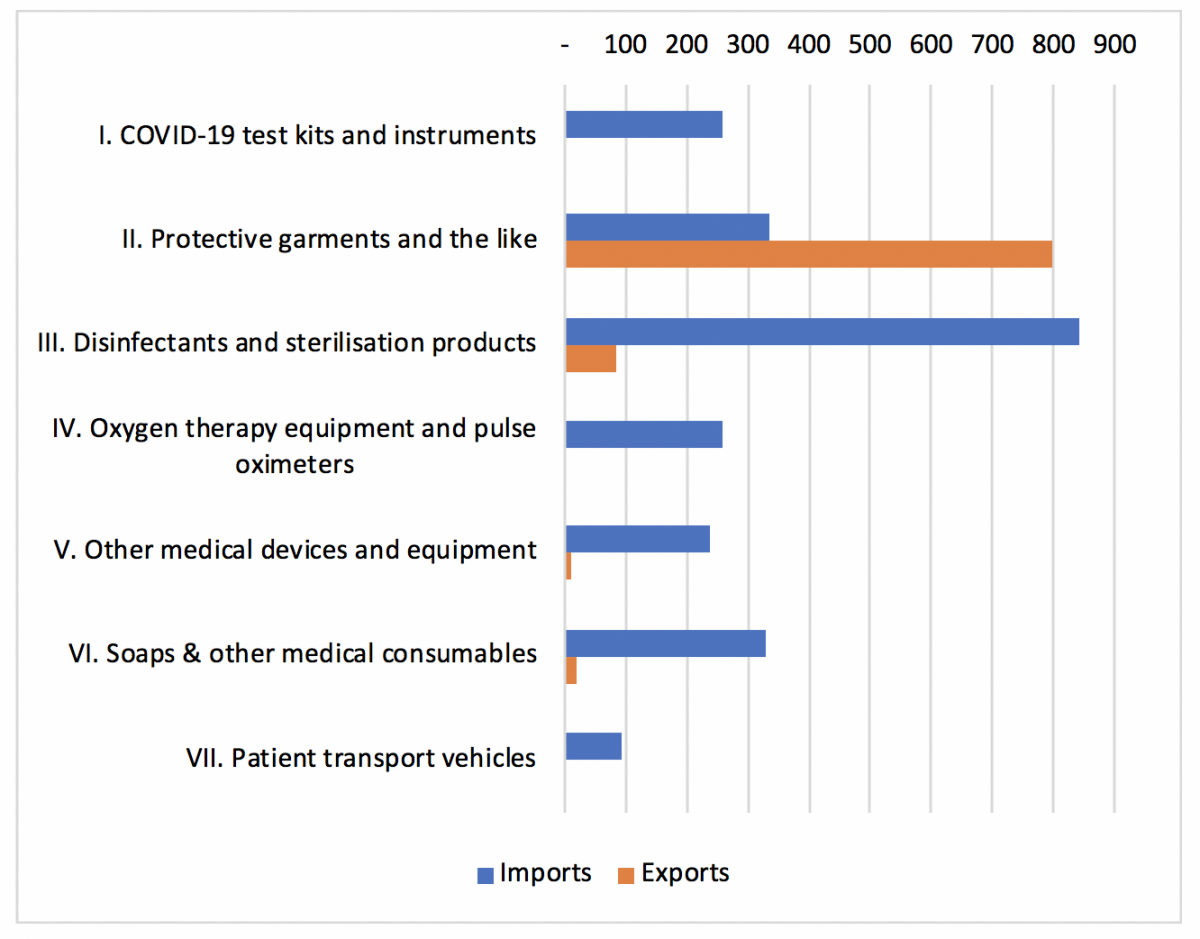

Commonwealth LDCs import a range of health-related products (see Figure 3). Large import items in 2018 were disinfectants, soaps, medical consumables and oxygen therapy equipment (e.g. ventilators, which can cost up to US$50,000 and are quite rare in LDCs). Despite having some manufacturing capacity, Bangladesh imported comparatively more PPE than the other LDCs, given the significantly larger population and healthcare needs. However, medical devices, oxygen therapy equipment and COVID-19 test kits were not widely imported by African LDCs, which may have affected their preparedness in tackling the pandemic.

Figure 3: Composition of health-related imports in Commonwealth LDCs

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

Note: The analysis uses products identified in WCO’s list of medical supplies version 2.1

Commonwealth LDCs have various sources of medical supplies and depend less on the EU and the USA compared to other Commonwealth developing countries. Most LDCs source around 10-25% of their supplies from a single supplier, except Lesotho and Malawi, which source around 65% of all supplies from South Africa and 57% from India, respectively. Lesotho has more than 80% reliance on neighbouring South Africa for PPE and oxygen therapy equipment.

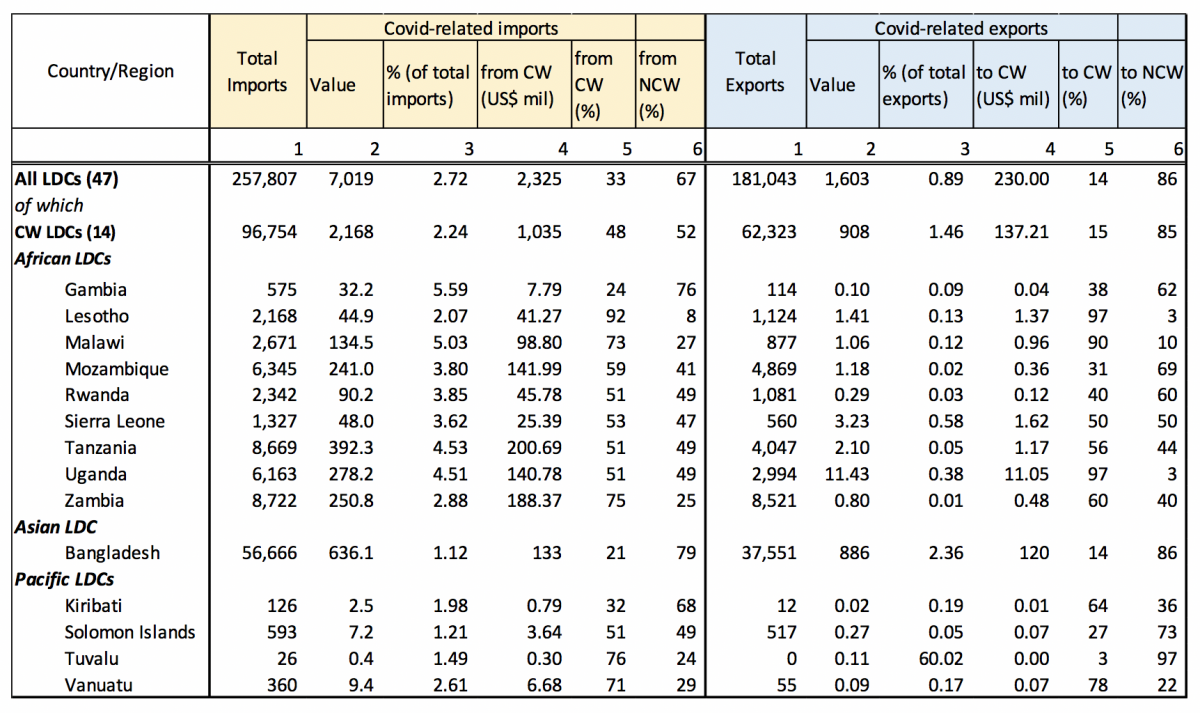

There is significant intra-Commonwealth trade, with LDC members sourcing around half of their COVID-19-related imports from Commonwealth countries (see Table 2). For African LDCs, India and South Africa are the leading suppliers. South Africa is the main supplier of PPE while the EU sells test kits and ventilators. Bangladesh, the only Commonwealth LDC in Asia, looks regionally to China and India for supplies. Given their small size and geography, the Pacific LDCs depend on Australia to supply all COVID-19 products, especially ventilators (86%). India and New Zealand are also top exporters to Pacific LDCs.

Table 2: Relative importance of intra-Commonwealth trade for COVID-related medical supplies

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

Recommendations

It is unrealistic to expect LDCs to develop self-sufficiency in medical supplies. Except for Bangladesh, which produces some PPE, most LDCs lack basic manufacturing facilities. Similarly, significant fiscal measures to strengthen healthcare, expensive airlifting of supplies (especially for landlocked LDCs), and industrial repurposing are not viable policy options for most LDCs. Instead, a globally coordinated approach would better ensure that LDCs are adequately prepared to mitigate current and future waves of infection. Ramping up globalised production can help satisfy the spike in demand. Equitable access to COVID-19 health technologies through pooling of knowledge, intellectual property and data as envisaged in the WHO’s ‘Solidarity Call to Action’, as well as mobilising manufacturers to work together like the Tech Access Partnership of the UN Technology Bank for LDCs, are the best policies to help LDCs navigate this crisis.

Second, maintaining undisrupted trade in medical supplies – and refraining from export bans – is imperative, as the LDC Group at the WTO has called for. The decision to impose temporary restrictions might be consistent with WTO rules, however, as major producers contain the virus and ease their lockdowns, excess medical supplies can be diverted to LDCs.

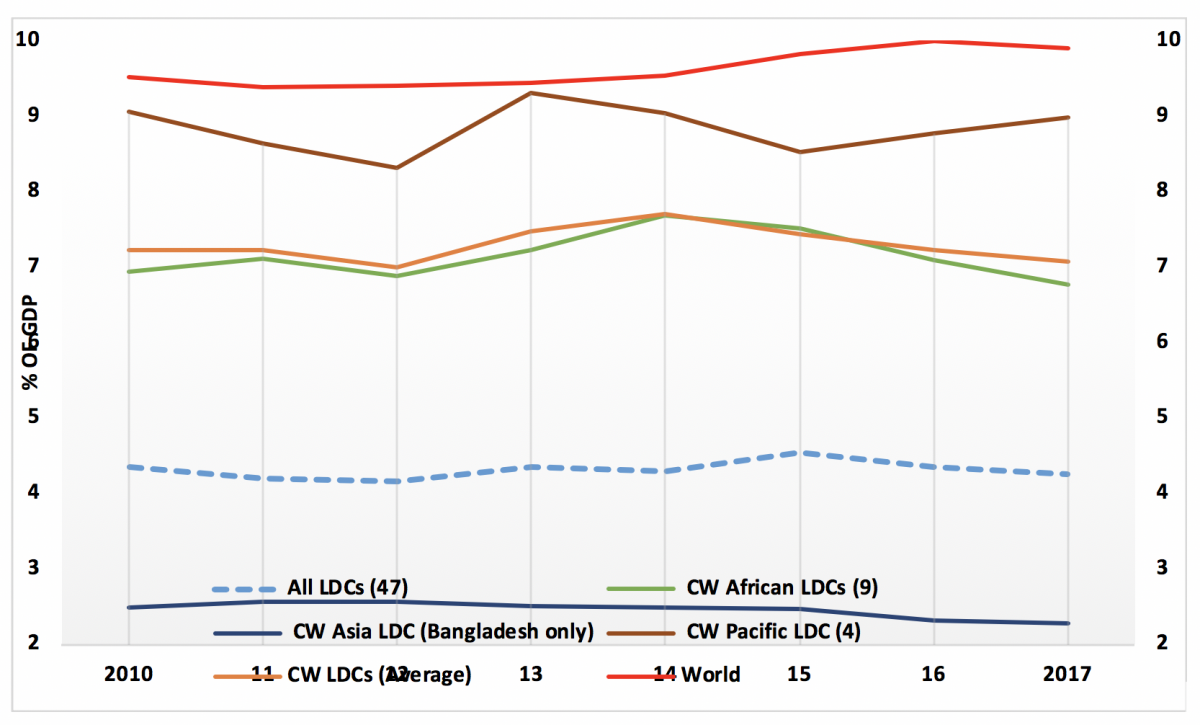

Third, the international community should redouble their efforts to help strengthen healthcare systems in LDCs in line with SDG3. Healthcare expenditure in LDCs is very low, especially in Bangladesh, which is the most populous LDC (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Healthcare expenditure in LDCs (% of GDP)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WDI)

-------------------------------

[1] The 47 LDCs have a total population of 1.1 billion, of which 350 million live in the 14 Commonwealth LDCs (see Table 2 for the list of Commonwealth LDCs).

[2] LDCs' share of health-related exports is quite negligible, less than 0.25%, and way lower than their share of global merchandise export (about 1%).

Header image of a soy, corn and groundnut farmer working his fields in Malawi - ©Ollivier Girard/EIF

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.