|

|

|

Economic transformation returned to the international development agenda because of the Great Recession.

The 2008 financial crisis revealed the limits of unfettered market-based approaches and highlighted the key role states must play in regulating market forces. This renewed ambition of higher levels of economic productivity also permeates the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with its calls for economic growth in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8, and inclusive and sustainable industrialization in SDG 9. Least developed countries (LDCs) show limited competitive productive capacity in all economic sectors as stressed, amongst others, in the 2011 Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA).

What an LDC produces and trades shapes more than just its economic growth. It also affects its capacity to generate jobs, distribute rents among the population and catch up with more advanced economies. Thus, a country's production structure affects its sustainable development trajectory.

At present, LDC transformation is hampered by production concentrated in a handful of economic activities with low value addition, exports going to relatively few countries, weak institutions, infrastructure gaps and low levels of private sector investment. On top of this, LDCs tend to suffer more from exposure to natural disasters and climate change impacts.

All 38 of the 47 LDCs that participated in a 2019 joint OECD-WTO aid-for-trade monitoring exercise prioritised the transformation of their economy. Policies are focussed on creating the right incentives for economic diversification and structural transformation. Limited industrial or manufacturing capacity, followed by inadequate network and transport infrastructure and restricted access to finance are identified as the main barriers. Donors also highlighted a lack of skills as an impediment to the economic transformation of LDCs.

Despite some broad commonalities, LDCs encompass diverse groups of countries: landlocked (e.g. Uganda, Bhutan), small developing islands (e.g. Vanuatu or Timor-Leste), natural resource rich economies (e.g. Angola and Guinea), and countries that have started to engage in export-led and job-rich manufacturing (e.g. Ethiopia, Bangladesh). Thus, the good news is that production transformation is doable.

Tackling binding institutional, human, hard and soft infrastructure constraints will allow shifting from low value-added specialisation patterns to higher ones. While there is no easy panacea, enabling a process of “self-discovery” to identify future opportunities for more sophisticated or new products and services is an essential component.

How can a process of "self-discovery" shape future opportunities?

Assessing existing assets and capabilities is crucial, but it is equally important to initiate a process of strategy setting and consensus building among different parts of society. Designing a national strategy through a participatory process helps to develop shared aspirations within the country.

A successful national development strategy entails a vision for the future that targets actions, allocates budgets to achieve the vision, and employs a monitoring and evaluation approach to assess results and provide feedback. Success stories show that a mix of five capabilities have been crucial in the process of production transformation and upgrading (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The five features of success for transformation and upgrading

Source: OECD Production Transformation Policy Review (PTPR) framework in OECD (2017)

The IPoA, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the SDGs call for aid for trade, including through the Enhanced Integrated Framework, to support LDC production transformation ambitions.

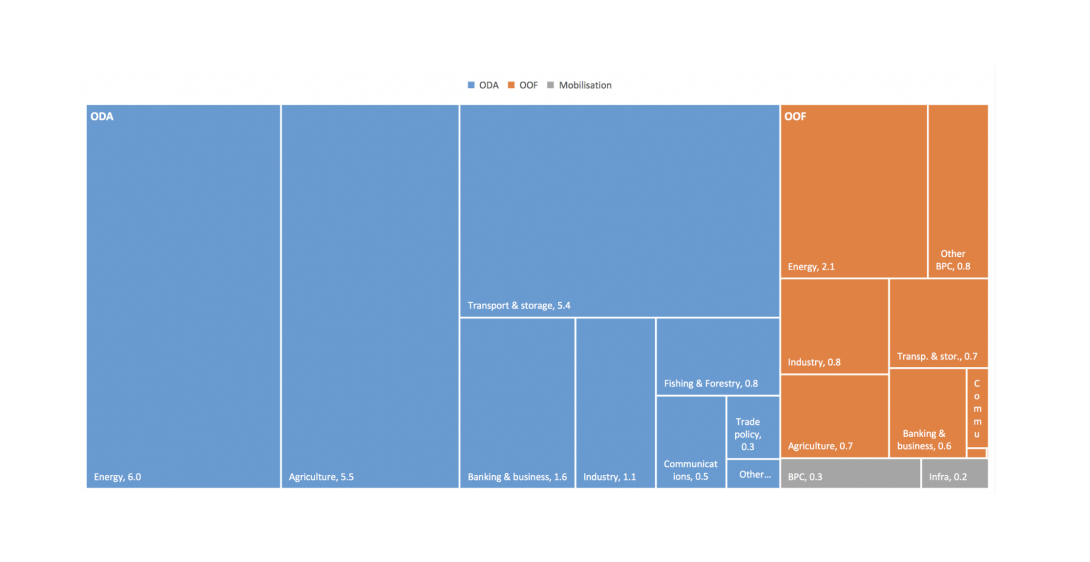

In 2018, donors committed US$21 billion in aid to trade-related projects and programmes in LDCs. This corresponds to 76% of total trade-related development finance to LDCs. The remainder was committed in the form of low concessional other official flows (US$6 billion) and private finance that was mobilised through official interventions (US$0.5 billion). Aid for trade commitments to LDCs increased annually by an average of 11.4% since the Aid for Trade Initiative was launched in 2006, while per capita disbursements more than doubled to US$13 in 2018. This is twice the amount for all developing countries. In LDCs, a higher share of aid for trade supports building productive capacities (42.4%) than other developing countries (25.5%) where infrastructure is the dominant aid for trade category (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trade-related development finance to LDCs in 2018, US$billion (commitments of Official Development Assistance (ODA), Other Official Flows (OOF) and private finance mobilised by official interventions)

Support for trade-related adjustment has been small and commitments only amounted to US$13.7 million since 2007. Although there is no sector code for economic diversification in the DAC-Creditor Reporting System, a keyword search shows that activities covering economic diversification issues in LDCs also only amounted to a total of US$108 million between 2006 and 2018.

The need for more aid for trade and private finance

Aid for trade helps bring about economic transformation when it supports those LDC governments that base their development strategies on their comparative advantages. Findings show that when the donor community aligns their aid around those kinds of priorities, economic transformation occurs. But, even when structural transformation is a priority for governments that are intent on promoting sustainable development, aid for trade alone is too small to finance those efforts fully.

Also, too little private finance is invested in the LDCs. Blended finance - when appropriate and carefully deployed - might offer alternative financing solutions. However, getting blended finance to work for LDCs requires alignment around national priorities that are part of broader SDG financing strategies.

More importantly, the growing use of blended finance should not result in a decline in the flow of concessional development finance. LDC governments must be vigilant about the risks associated with different financing modalities, including debt sustainability. This requires official finance providers to offer their financing on appropriate terms and conditions.

----------------------

Aussama Bejraoui, Elisabeth Lambrecht and Frans Lammersen work in the OECD on development issues. The views expressed do not represent those of the organisation.

Header image of a man working on the construction of a hotel in Saleapagaa Village, Upolu Island, Samoa - ©Asian Development Bank via Flickr Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.