|

|

|

Despite commendable progress implementing the Istanbul Programme of Action (IPOA) for Least Developed Countries (LDCs), structural vulnerabilities in LDCs continue to exist and warrant urgent attention. Many LDCs have limited productive capabilities, rely heavily on exports of a narrow range of primary commodities, and face high and unstainable debt levels. Pressing challenges related to climate change and the health and economic crises created by the COVID-19 pandemic are exacerbating these vulnerabilities.

COVID-19 threatens to stall, or even reverse, the economic transformation gains already achieved by LDCs and stifle the prospects of countries looking to graduate out of the LDC category. The global economic recession and ensuing job losses may push large shares of workers towards lower-productivity jobs or into informal sector work. This could result in a sustained shift in resources towards low-productivity primary sectors and low-value-added activities. Women and youth, less-skilled workers and those living in rural areas will be disproportionately affected, impacting progress towards inclusive economic transformation.

Urgent action is required to address these vulnerabilities. Here is why and how.

LDCs have limited productive capabilities

Economic activities in LDCs are insufficiently diversified and mostly concentrated in low-value-added primary production or low-productivity services. They have made little progress in enhancing productive capacity and generating structural economic transformation.

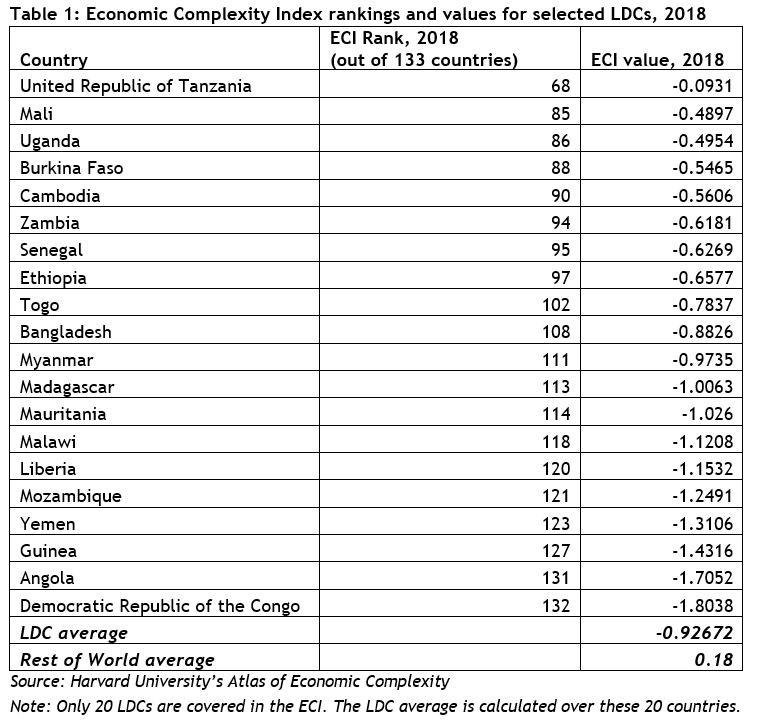

Table 1 presents individual values and rankings for LDCs on the Economic Complexity Index (ECI). Countries with higher ECI values have more sophisticated and specialised productive capabilities and are able to produce a highly diversified array of complex products for export. Six LDCs rank among the 10 countries with the lowest levels of economic complexity. All LDCs included have ECI values below the global average.

LDCs rely heavily on exporting a narrow range of primary commodities

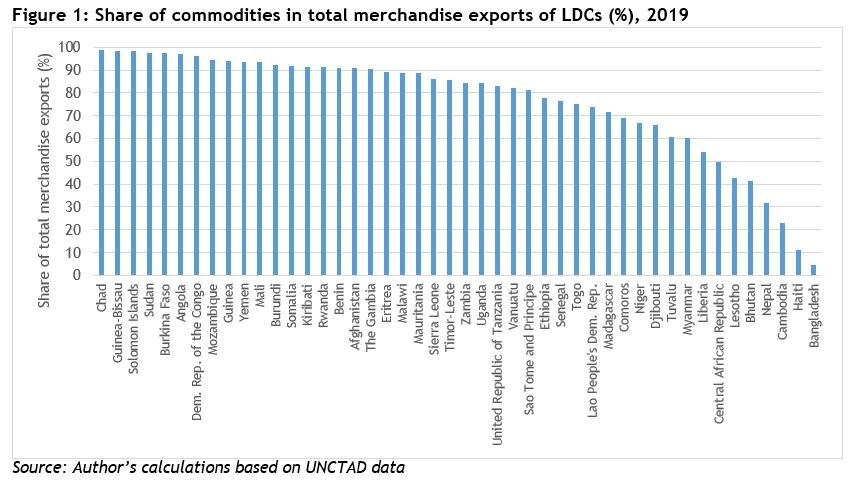

The share of commodities in total merchandise exports exceeded 80% in more than half (28) of the 47 LDCs in 2019 (see Figure 1), and was higher than 90% in 18 of them, including five Commonwealth LDCs (The Gambia, Kiribati, Mozambique, Rwanda and Solomon Islands). Commodities contribute less than half of all merchandise exports in only seven LDCs (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Haiti, Lesotho and Nepal). In Bangladesh, they account for only 4.8% of merchandise exports, pointing to a much higher degree of diversification. On average, the share of commodities in total merchandise exports across the 14 Commonwealth LDCs is 77.3% (compared to 75.8% for non-Commonwealth LDCs).

LDCs contributed under 1% of global merchandise exports in 2018. Their participation in global trade in services is also low, and concentrated in only a few sectors. This is indicative of a wider pattern of marginalisation in world trade.

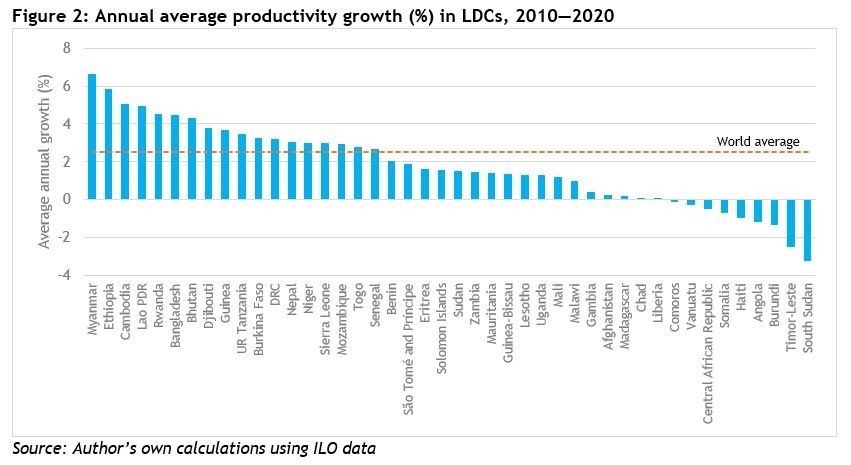

Economic transformation in LDCs through diversification away from low-value-added primary production and greater participation in global trade is hamstrung by limited productivity growth, although there is considerable variation across the LDC group (see Figure 2). Average productivity growth from 2010-2019 was below the world average (2.5%) in 27 LDCs, and negative in Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Haiti, Somalia, South Sudan, Timor-Leste, Vanuatu and Yemen.

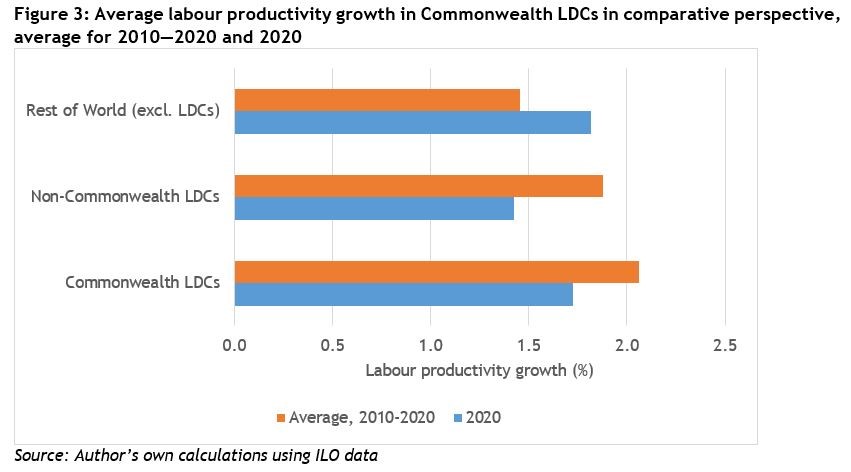

Some LDCs fared better. Over the past decade, labour productivity growth exceeded the world average in 18 LDCs, and was relatively high in Myanmar (6.6%), Ethiopia (5.8%), Cambodia (5%), Lao PDR (4.9%), Rwanda and Bangladesh (both 4.5%). Commonwealth LDCs outperformed their non-Commonwealth counterparts and non-LDCs (see Figure 3) ― labour productivity grew by 2.1%, on average, in Commonwealth LDCs, compared to 1.9% in non-Commonwealth LDCs and 1.5% in non-LDCs. However, non-LDCs have marginally outperformed Commonwealth LDCs in productivity growth so far during 2020 (1.8% versus 1.7%).

Many LDCs face high and unsustainable debt levels

External debt levels in developing countries are at an all-time high and rising due to COVID-19. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has classified 14 LDCs as under high risk of debt distress, including six Commonwealth members: The Gambia, Kiribati, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Tuvalu and Zambia.

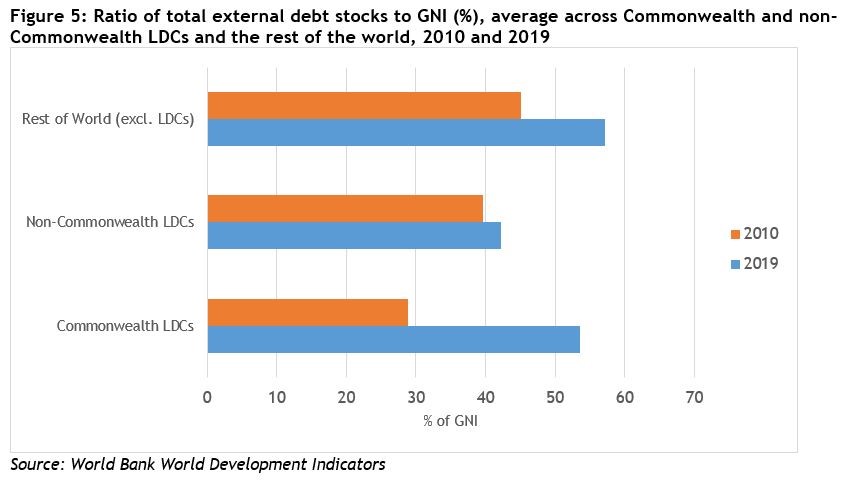

Even prior to the emergence of COVID-19, external debt stocks were very high in several LDCs and exceeded 100% of gross national income (GNI) in Mozambique, Sudan and Zambia in 2019 (see Figure 4). When considered collectively, the ratio of external debt stocks to GNI increased markedly, on average, in Commonwealth LDCs over the past decade (see Figure 5).

Tackling LDC vulnerabilities

As experts and policy makers look ahead to the Fifth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries (UN LDC5) in 2022, focus must shift to addressing four key LDC vulnerabilities.

First, LDCs need to develop productive capabilities in higher-productivity sectors and to shift resources from low- to higher-valued-added activities within and between sectors. Such structural economic transformation is crucial for sustained development and poverty reduction, and key to building greater resilience.

Second, digital divides within LDCs and between LDCs and other countries need to be closed. Doing so requires enhancing digital literacy, promoting digital connectivity, investing in digital infrastructure and ensuring access to digital technologies. This can be delivered through coordination between the public and private sectors in LDCs, supported by multi-stakeholder digital cooperation involving civil society organisations, development partners and international institutions.

Third, governments need to resist protectionism and maintain commitments to free, transparent, inclusive and rules-based trade in order to boost LDC participation. The multilateral trading system must take into account the special requirements of LDCs and small and vulnerable economies.

Finally, more needs to be done to enhance debt sustainability and de-risk, incentivise and improve access to finance for LDCs. This will require bold and systemic solutions to debt relief spearheaded by the G20, Paris Club, World Bank and IMF, as well as innovative and accessible financing mechanisms ― including blended finance and climate finance ― provided by governments, private corporations and domestic, regional or multilateral development banks.

--------------

The author gratefully acknowledges excellent comments and suggestions provided by Dr. Salamat Ali on earlier drafts of this article.

---------------

Dr. Neil Balchin is an Economic Adviser at the Commonwealth Secretariat.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.