The government of Uganda put containment measures in place to tackle COVID-19. These included quarantines; bans on public gatherings and weekly markets; closures of schools, borders and nonessential retail outlets; and the suspension of international flights.

These measures have negatively affected Ugandan businesses that deal in agriculture, with 71% of agricultural firms reporting a severe decline in demand. This has threatened future economic growth and inclusion in the country, since agriculture is a key sector, contributing to 25% of GDP, about 50% of export earnings and 70% of employment.

During the pandemic, digital technologies have emerged as key pathways to mitigating economic losses, and the agricultural sector is no different. E-commerce for agricultural businesses, for instance, can enable market access during the pandemic, fuelled by social distancing measures and the shift to cashless transactions and mobile money.

But will African countries benefit from agricultural digital platforms (ag-platforms) or will the pandemic exacerbate the existing digital divide in access and use of these platforms?

A new paper from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) reveals important insights on this question, using a farmer-level survey in Uganda.

Uganda makes for an important case study given that most Ugandans live in rural areas and farm, with women making up 75% of the total farm labour. At the same time, almost half (45%) of the heads of smallholder farming households are under the age of 40.

Ag-platforms can serve as marketplaces, or virtual intermediaries that match buyers and sellers, and business-to-business (B2B) trading and sharing platforms. Farmers can also share knowledge of best practices and post experiences with ag platforms online, which can be shared with other farmers and stakeholders.

The proliferation of ag-platforms in Uganda has been home-grown: several local entrepreneurs have developed and run successful ag-platforms. Analysis in the paper draws from a survey of 821 farmers in Uganda who are using any of the four digital platforms – a Ugandan government-owned app called E-Voucher, and private sector-owned apps MUIIS, KOPGT and EzyAgric – complemented with stakeholder insights gathered through interviews with a range of actors. In terms of enrolling and using the platform, 40% of farmers are receiving support from the ag-platform itself, and 20% are receiving support from leaders of farmers’ groups or cooperatives.

Ag-platforms increase productivity and market access but offer low opportunities for product diversification.

Over 70% of platformised farmers in our survey report access to productivity-enhancing services such as agricultural training on planting, fertiliser use, post-harvest maintenance and health and safety, compared to less than 45% of non-platformised farmers. This difference in access to services also translates into a yield differential; the average crop yield of maize producers on platforms is higher (by 18%) as compared to non-platformised maize producers.

The top reason to register on ag-platforms is to find new buyers, cited by 20% of platformised farmers, which has become even more difficult during the pandemic. Ag-platforms have been somewhat successful in achieving this; 23.44% of platformised farmers have diversified into new markets, compared to only 19% of non-users. However, a lower percentage of users have diversified into new products compared to non-users, questioning the ability of ag-platforms to promote product diversification.

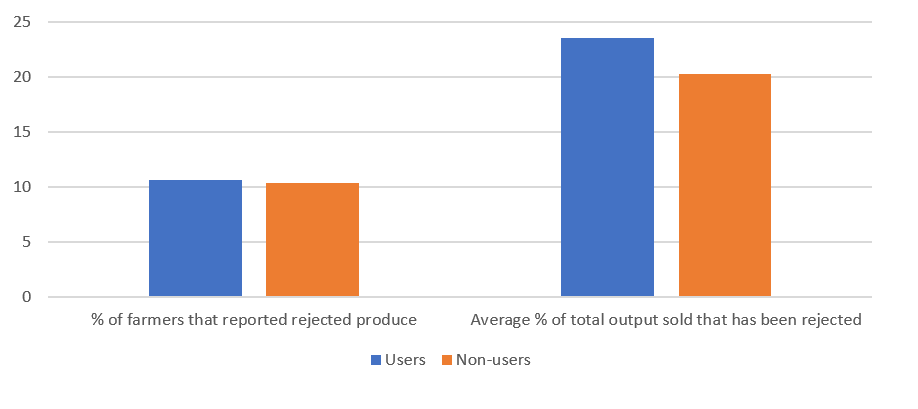

Interestingly, as Figure 1 depicts, the share of platformised farmers that report incidence of their produce being rejected is marginally higher than non-platformised farmers, with the average share of total output rejected also being high for platformised farmers. This suggests that farmers on platforms are selling to buyers who have higher standards and reject more produce, further indicating the need for ag-platforms that provide effective monitoring and oversight during the grading and aggregation of products post-harvest.

Figure 1: Rejection of produce, users versus non-users (% of farmers)

Women farmers are doing better on platforms but a dual gender digital divide still exists

Platformised women farmers are doing better than those who are not; only 12.5% of female platformised farmers report no access to training, compared to 46% of female non-platformised farmers. Women on platforms also seem to have higher access to formal work than women who are not on platforms; 21% are given a contract for their produce and 49.5% have access to working capital loans, as compared to 9.32% and 29% of non-platformised female farmers respectively.

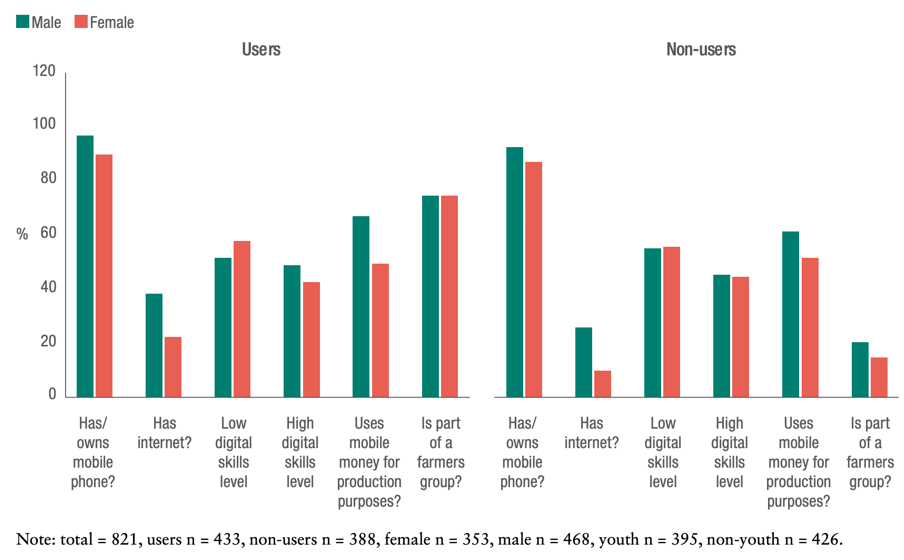

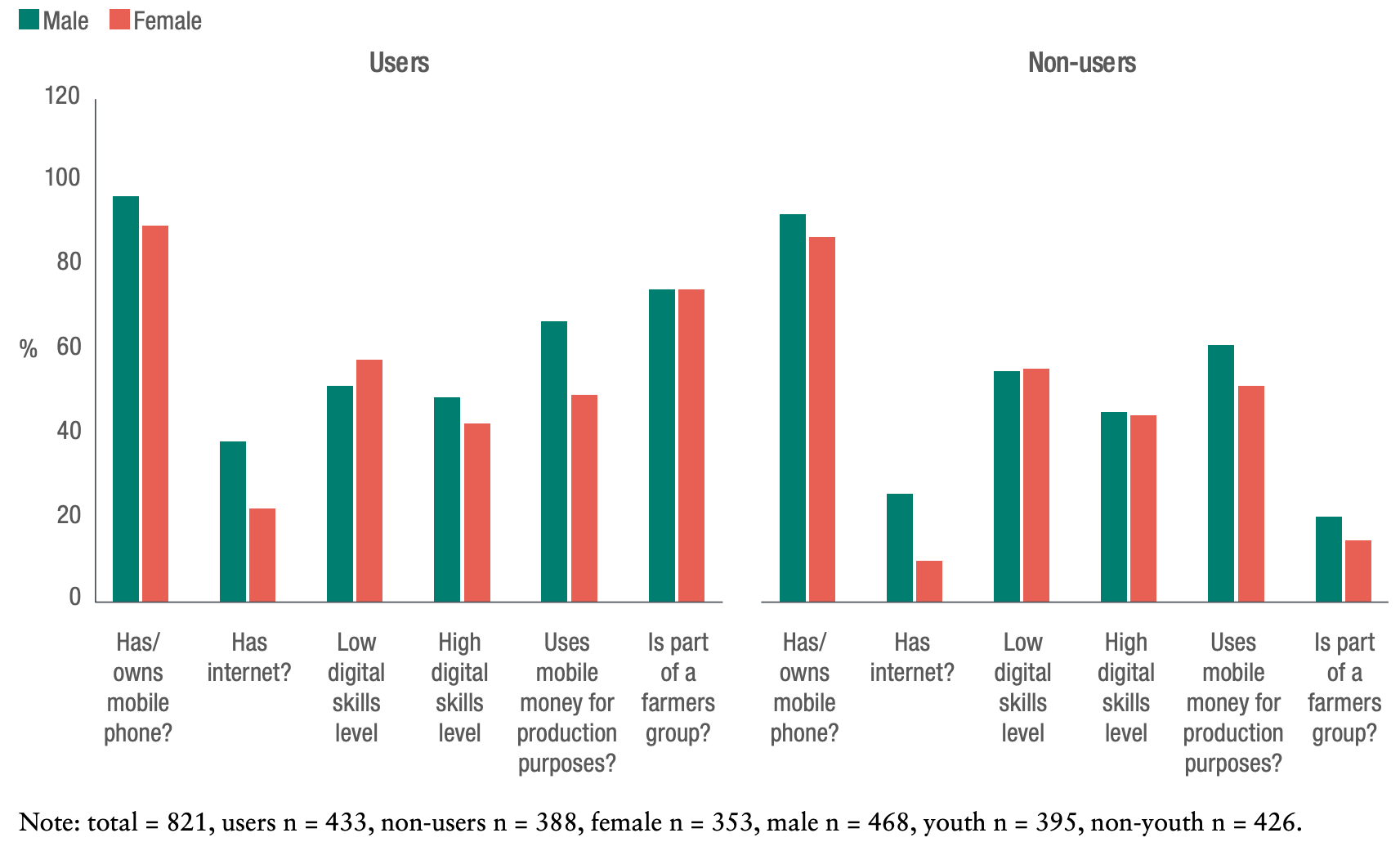

There seems to be ‘dual’ gender digital divide in platforms. Firstly, a lower share of female platformised farmers – 22% – have access to internet as compared to 38% of male users (Figure 2). Secondly, in some cases, such as maize producers, male platformised farmers are found to be more productive than female platformised farmers. The digital gender divide is likely being exacerbated by other major challenges, such as lack of tenure security, informal institutional constraints and intra-household dynamics. As Figure 2 shows, one way of increasing women’s participation can be through targeting increased women’s participation in farmer groups. Interestingly, a small number of women who had no access to a phone were able to access platform services through village agents, but this was possible only every two weeks or once each month, potentially missing out on real-time services.

Figure 2: Digital divide in ag-platform accessibility and use

Platformised youth are faring better but need targeted support during COVID

The data show that farmers under the age of 35 were more likely to be registered on an ag-platform compared to older cohorts, and that more employment was generated as a new class of youth leader emerged. These are educated youth who act as intermediaries between farmers and the ag-platform, helping other farmers to register and exchange information between the parties involved. Compared to non-users, platformised youth are doing better; 17% of young platform users receive a contract for the produce, compared to 14.5% of young non-platformised farmers in the sample.

Banga et al.’s (2020) forthcoming paper offers insights on ag-platform use and COVID. Of 350 Ugandan youth entrepreneurs involved in agricultural value chains that are surveyed, 70% rank ‘lack of awareness of digital apps’ as the primary obstacle in using ag-platforms. The youth that are on ag-platforms, however, report increased use of ag-platforms during COVID, mainly for finding information on COVID support and to get more information and to contact buyers and sellers online.

Recommendations for leverging ag-platforms for post-crisis recovery

A key recommendation is to ensure institutional oversight so that platformised farmers are able to meet the higher standards of buyers. Investments therefore need to be targeted towards ag-platforms that support improvements in the quality standards of produce, provide monitoring during production and sale, and perform evaluations. Second, is to improve storage and logistical facilities, which are key in moving products within a value chain, i.e. from farm gate to the intermediary/buyer and further downstream. Third, there is need to increase the effectiveness of farmers’ groups, and particularly women’s participation in these groups. Fourth, there is a need to address gender gaps and youth participation in accessibility and use of ag-platforms through targeted skills development initiatives on digital skills and trainings on agricultural practices.

________

Dr. Karishma Banga is a Research Fellow at the International Economics Development Group at ODI.

Header image - ©Simon Hess/EIF

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.