|

|

|

In 2030, most of the world’s poor will live in fragile contexts.

Fragility is a complex, context-specific and difficult to define concept. Of the 47 countries on the UN list of least developed countries (LDCs), 18 identify themselves as fragile and have signed the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States under the g7+ – a group composed of 20 countries that share experiences and advocate for country-led and country-owned processes in addressing fragility and conflict.

Fragility is identified by the g7+ as a spectrum of five stages: crisis, rebuild and reform, transition, transformation and resilience. These stages span five peacebuilding and state building goals: legitimate politics, security, justice, economic foundations and revenues and services. The principles of this new deal are captured in Sustainable Development Goal 16 calling for peace, justice and strong institutions.

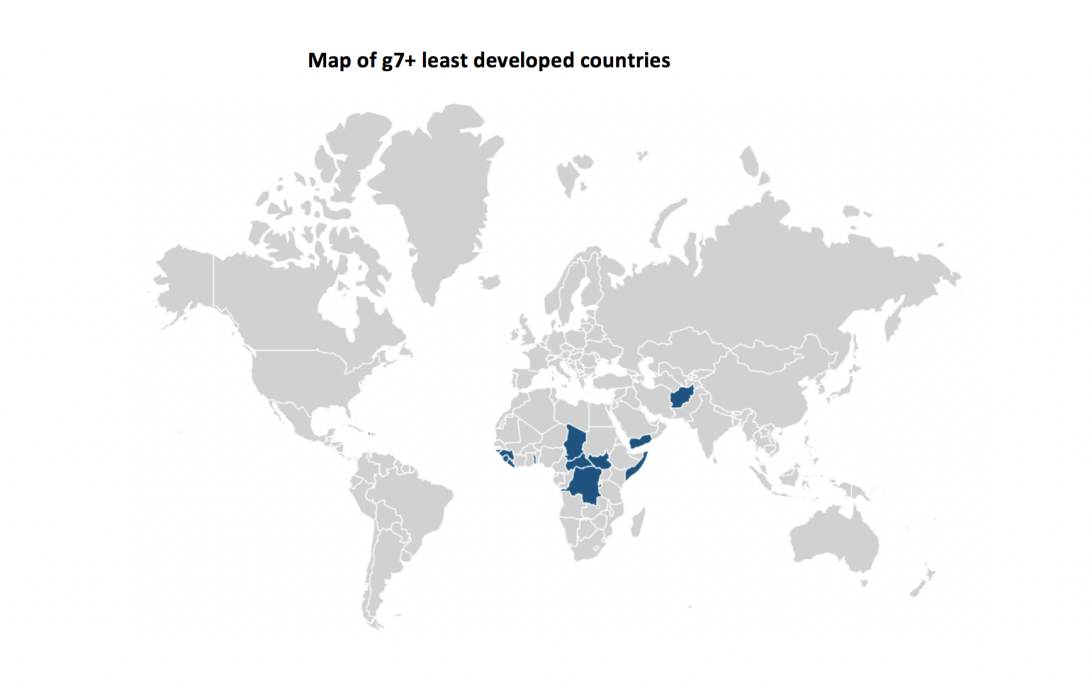

Map of g7+ least developed countries

Source: g7+ Secretariat

Note: The g7+ LDCs are: Afghanistan, Burundi, Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Liberia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo and Yemen.

Diversifying exports for greater stability

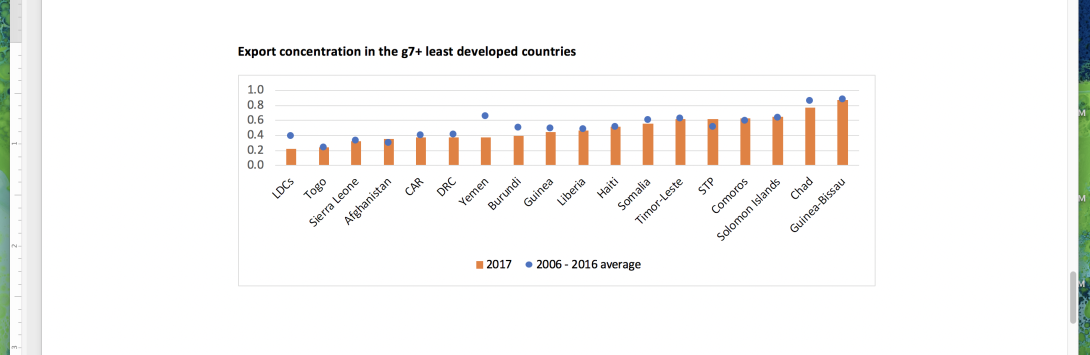

In fragile contexts, certain key structural features of LDC economies are more pronounced. The relative importance of trade is higher and exports tend to be even more concentrated in a few commodities. The top three export products in these economies represent over 40 percent of merchandise exports, reaching up to 99 percent in South Sudan.

Consider the drastic fluctuations of commodity prices over the past 10 years. The volatility of trade flows can have destabilising effects. The composition of exports in certain valuable commodities may provide incentives to fight for as well as undermine state institutions and thus the quality of public policies, including to promote a good business environment for private sector development and economic diversification.

Whether instability arising from fluctuations in trade flows translates into conflict depends, however, on contextual factors. So for g7+ LDCs, economic diversification can serve as a contributing factor for greater stability.

Further, policies that promote inclusion and reduce inequality enhance the resilience of societies to the risk of conflict. Policy and regulatory efforts can, for example, direct firm incentives towards productive rather than rent seeking activities and improve transparency. Supporting small and medium-sized enterprises can help ensure that the benefits of economic growth are more broadly shared.

Greater economic, social and political participation of youth and women is instrumental for greater stability. When women are included in peace processes there is a 35 percent increase in the strength of peace agreements lasting at least 15 years.

"The Chadian economy is mainly based on cash crops (especially cotton) and extractive industries (mining and oil). The strong economic growth – 7.4% between 2003 and 2015 – was mainly due to the use of oil resources. The country is extremely vulnerable to the external shocks including fluctuation of commodity prices. To diversify its economy, Chad will rely on sectors with high export potential including leather, sesame and gum arabic identified in the DTIS Update of Chad," said Djabre Dadi from Chad's Ministry of Mines, Industrial Development, Trade and Promotion of the Private Sector in his response to the aid for trade monitoring and evaluation exercise (AFT M&E) 2019.

"Improving organisation of those sectors will contribute to greater economies of scale thereby helping with greater integration into the global value chains,” he added.

Export concentration in the g7+ least developed countries

Source: UNCTADstat, accessed February 2019.

Note: Higher index values denote higher concentration of exports in a few products. The data for South Sudan is not available. CAR refers to Central African Republic; DRC to Democratic Republic of the Congo; and STP to São Tomé and Príncipe.

An enabling institutional and regulatory environment, adequate productive infrastructure and human capital have proven to be essential for economic diversification. Yet, these are areas undermined by fragility and conflict. The challenges of diversification are thus particularly acute in such contexts.

"The Democratic Republic of the Congo suffers from lack of infrastructure to support the production and marketing of goods and services, difficulties of ensuring the connectivity of different entities as well as the deficit in the supply of energy," said Charles Lusanda Matomina, the Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF) National Implementation Unit Coordinator at the DRC Ministry of Foreign Trade in AFT M&E 2019.

Joining forces

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Programmes to support economic and export diversification need to be cognizant of local contexts, build coalitions towards reform and contribute to broader state-building efforts. LDC governments are at the centre of their national economic diversification initiatives for private sector development, employment creation and poverty reduction.

The international development community also has a role to play. For the poorest countries, aid remains an important source of external financing. Yet, aid for trade flows are highly concentrated among a few recipients, development partners and sectors. This trend is even more pronounced for g7+ LDCs. For example, the top four g7+ LDCs receive over half of aid for trade flows to the group. This high level of concentration raises questions regarding the degree of adequate support directed at the remaining g7+ LDCs.

Indeed, finding better ways to support those who need it most has yet to be fully explored. The World Bank is developing its Future Strategy for Fragility, Conflict and Violence, while the International Monetary Fund is increasing its support to fragile and conflict-affected countries. These are encouraging developments in that new approaches and greater emphasis are being targeted at supporting fragile contexts.

The World Trade Organization's Seventh Global Review of Aid for Trade on 3-5 July 2019 offers a unique opportunity to brainstorm on how trade development work can contribute to delivering the global promise of leaving no one behind.

----------

* Luisa Bernal is Policy Specialist, Trade and Sustainable Development, United Nations Development Programme. Daria Shatskova is Programme Officer, Enhanced Integrated Framework.

--------

This policy series has been funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed in this publication are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.