|

|

|

Women’s economic empowerment has been recognised as one of the key drivers of sustainable development. When women have more control over household resources, it leads to greater investment in health and education for the family. Furthermore, it results in higher and more sustainable levels of growth, which is extremely important for least developed countries (LDCs). In this context, two Sustainable Development Goals address women’s economic empowerment – Goal 5 on gender equality and Goal 8 on decent work and economic growth.

At the same time, women continue to face barriers to employment and often have less access than men to land, finance, machinery and technologies, contributing to gender gaps in income and productivity. Furthermore, while women can potentially benefit from enhanced trade, special attention needs to be paid to the negative impacts of trade liberalisation. For instance, export-oriented garment production has generated employment and wages for women in low-income countries, but fierce international competition has also fostered poor quality jobs.

Aid for trade can help enhance opportunities for women to participate in export and import activities – including through micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises – and thereby contribute to their economic empowerment. This gender-responsive support can further address impediments to trade, and also help prevent women from being negatively impacted when employed in export activities – due to poor labour conditions and low wages for example – through standard setting and training.

Gender responsive aid for trade is increasing but remains low overall

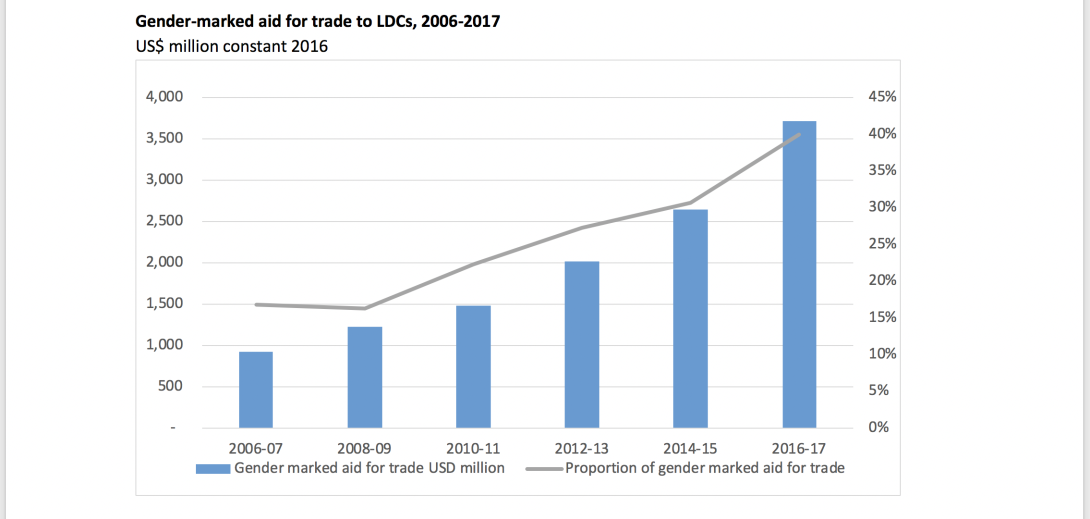

Gender-responsive aid for trade committed by bilateral donors to LDCs has increased from US$921 million in 2006-07 to US$3.7 billion in 2016-17 – an increase from 17% to 40% of total aid for trade. These sums and relative shares differ greatly by sector. In 2016-17, the sector with the highest amount of gender-responsive aid for trade was agriculture at US$1.7 billion; followed by transport at US$1 billion and energy at US$441 million.

Gender-marked aid for trade to LDCs, 2006-2017

Source: OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System: aid activity (accessed 25 January 2019)

Note: The data refer to Official Development Assistance and Other Official Flows; only Development Assistance Committee members for reasons of data availability.

When looking at the proportion of gender-marked assistance in total aid for trade commitments to different sectors in LDCs, agriculture was also the highest in 2016-17 at 71%; followed by trade policies at 48%. However, the share of gender-responsive aid in the infrastructure sectors was only 33% in transport, 20% in energy and 5% in communications.

In terms of recipient countries, the majority of LDCs with the highest share of gender-responsive aid for trade in 2016-17 were located in Africa – varying greatly from 88% in Yemen down to 41% in Rwanda. Given that 60% of total aid for trade directed at LDCs is not gender-responsive, there is considerable scope for improvement.

LDCs with the highest share of gender-responsive aid for trade, 2016-17

|

Countries |

Share of gender-responsive aid for trade (%) |

|

1) Yemen |

88 |

|

2) Eritrea |

70 |

|

3) Haiti |

60 |

|

4) Solomon Islands |

60 |

|

5) Tuvalu |

55 |

|

6) Somalia |

55 |

|

7) South Sudan |

52 |

|

8) Sao Tome and Principe |

49 |

|

9) Nepal |

48 |

|

10) Rwanda |

41 |

Source: OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System: aid activity (accessed 25 January 2019)

Good practices in promoting women’s economic empowerment in LDCs

There are numerous examples where donors incorporate gender perspectives in aid for trade. Many projects entail the training of women, either as government officials in policymaking or as project beneficiaries in enhancing income-generating activities. There are often targets or quotas to ensure that a sufficient proportion of trainees or employees from the domestic labour force are women. Other forms of support involve studies and the development of project design that seek to incorporate gender perspectives in particular areas of intervention or activity.

Canada, for example, is supporting Burkina Faso in rural electrification, particularly through the promotion of solar energy, as well as associated business development for women. The installation of photovoltaic panels will be used to increase the production, processing and storage of onion, chicken and fish, which are important economic activities in the region. The project is expected to benefit 40,000 people, especially women through the involvement of women’s groups.

Another example includes World Bank assistance to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic to facilitate trade by helping simplify business regulations and improve firm-level competitiveness. Specifically, the project supported the provision of free advisory services to businesses, including women-led enterprises, and the introduction of computers in provincial offices to allow for easier submission of documentation and registration. The results are to be measured by the increase in operating licenses in sectors of interest to women and the decrease in the number of procedures for businesses that were started by women.

An additional case worth highlighting is a joint project by USAID and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in Afghanistan focussed specifically on women working in the poultry value chain. The project aims to increase their income through intensive technical training on poultry rearing and vaccinations, as well as sustainable inputs such as feed and drugs, and the establishment of a marketing network of women to link village poultry producers to urban markets. After two years, the project had trained over 21,000 women in poultry management and organised 850 producer groups, with an evaluated increase in household income for over 15,000 female producers.

Looking ahead

While there are many positive examples of interventions like those described above, donors often still lack monitoring and evaluation systems with adequate indicators to assess impact. Such results-based monitoring systems would help obtain insights on what works – and what does not – for long-term sustainable outcomes regarding women’s economic empowerment. Donors would also benefit from a broader communication of impacts and results to help replicate good practices and improve programming with the objective of strengthening the gender dimension of aid for trade.

----------

* Marianne Musumeci is Research Advisor and Policy Officer at the OECD. Kaori Miyamoto is Senior Policy Analyst at the OECD.

--------

This policy series has been funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed in this publication are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.