|

|

|

As the world grapples to contain the novel coronavirus, another crisis of widespread hunger is looming in many developing countries, particularly the least developed countries (LDCs). Although there are currently no signs of a COVID-19-induced global food crisis, the World Food Programme (WFP) has warned of potential widespread hunger that could push an estimated 265 million people to the point of starvation.

The effect is likely to be more pronounced in the world’s most impoverished nations, which depend on imported food products to ensure requisite food levels and maintain food security. Two Commonwealth LDCs, Bangladesh and Mozambique, are among the world’s 25 hunger hotspot countries.

LDC food import dependence

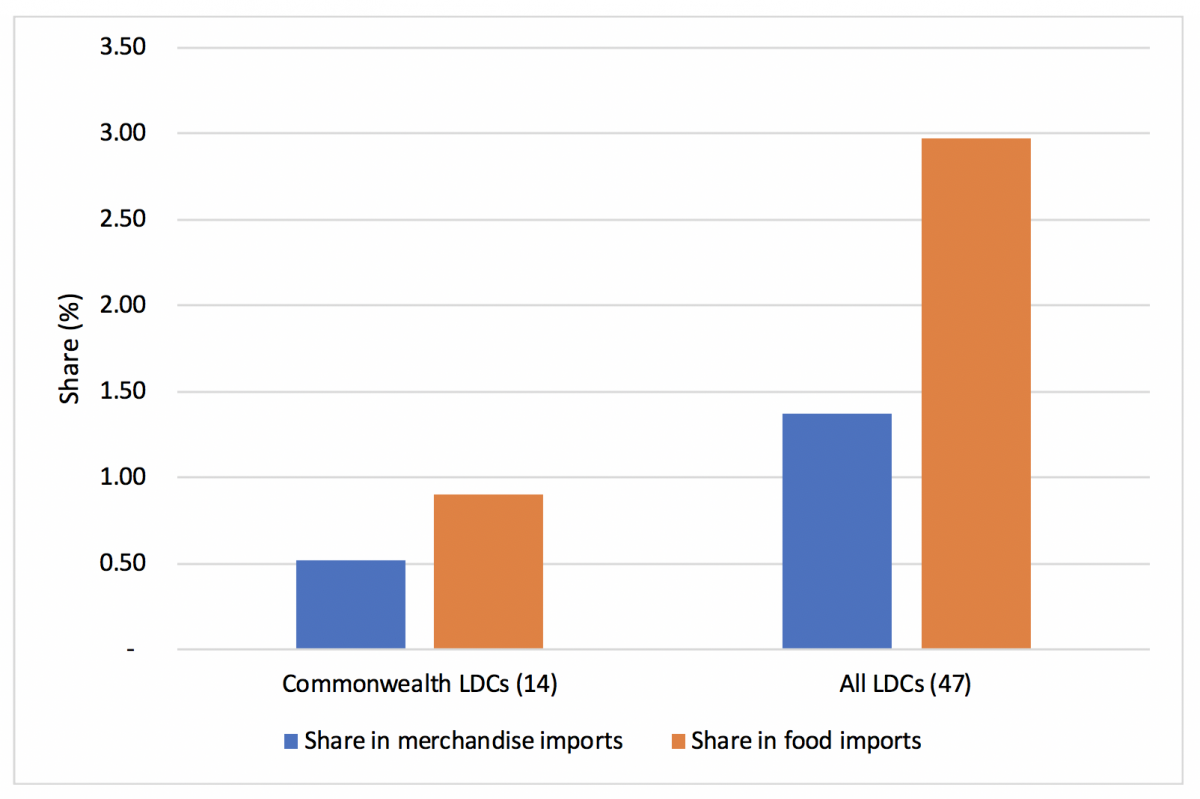

LDCs account for around 3% of global food imports, which is almost double their share of merchandise imports (1.45%). This import dependence makes LDCs extremely vulnerable to any disruptions in global food production and supply chains (see Figure 1). Maintaining open and functional supply chains is therefore imperative to avoid shortages of essential food items.

Figure 1: LDCs’ share of global food trade (%, 2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

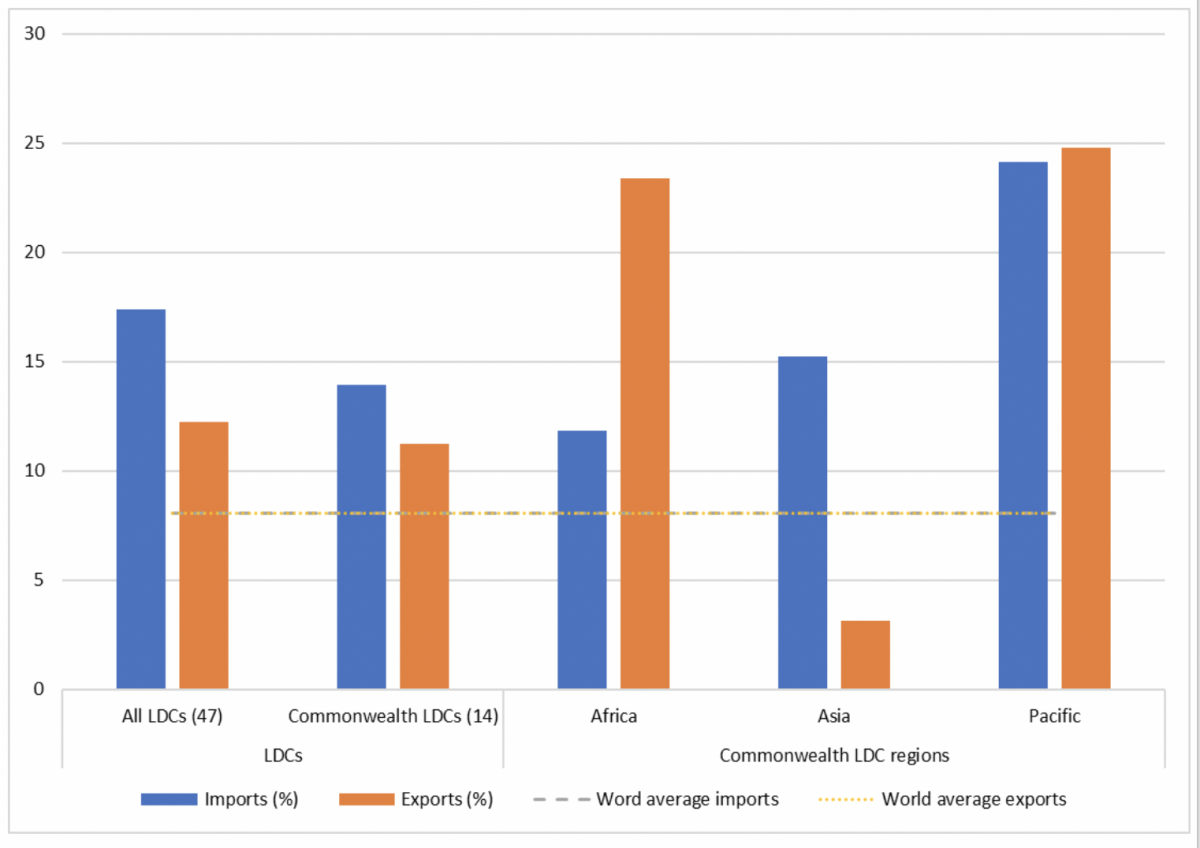

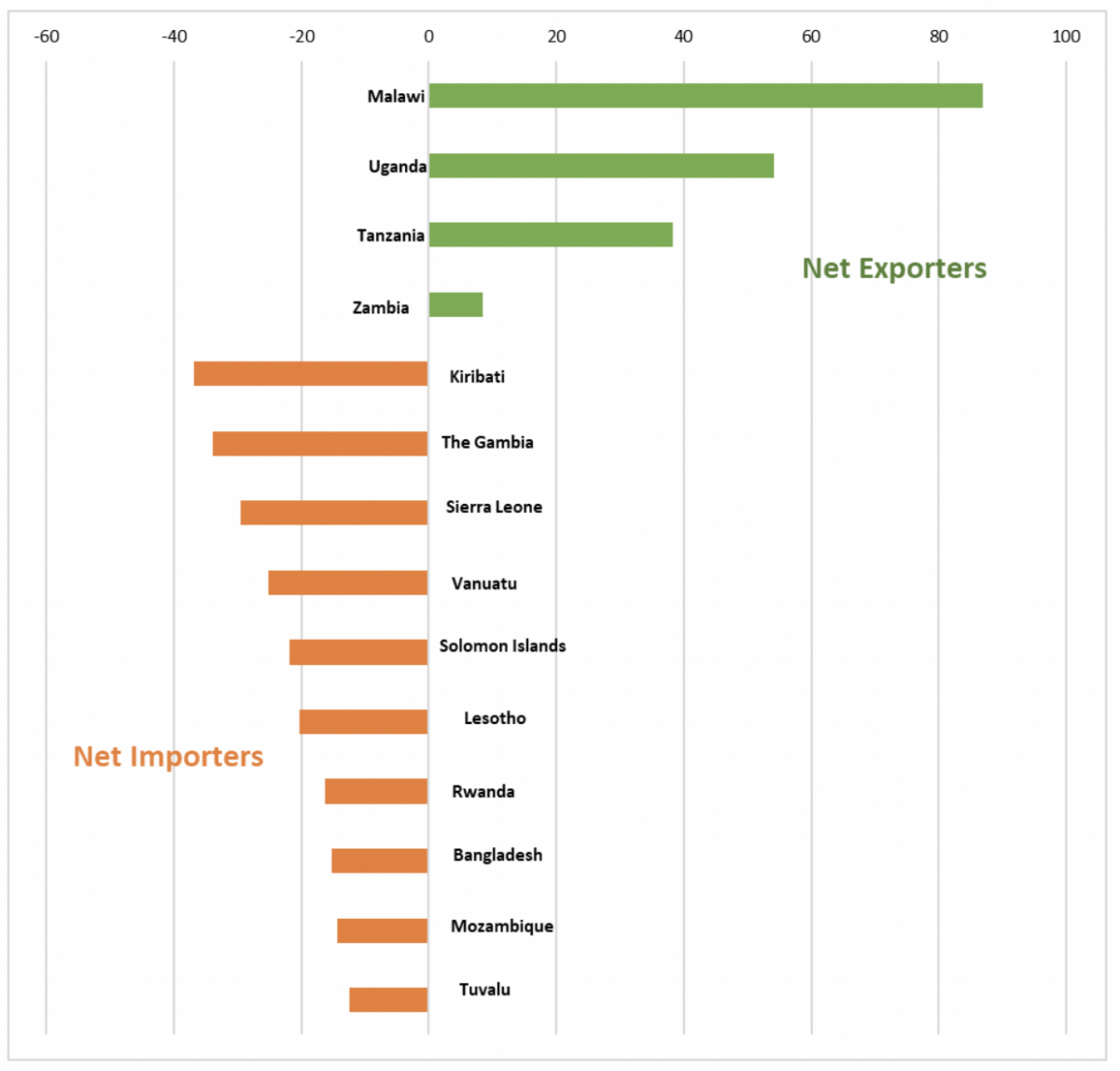

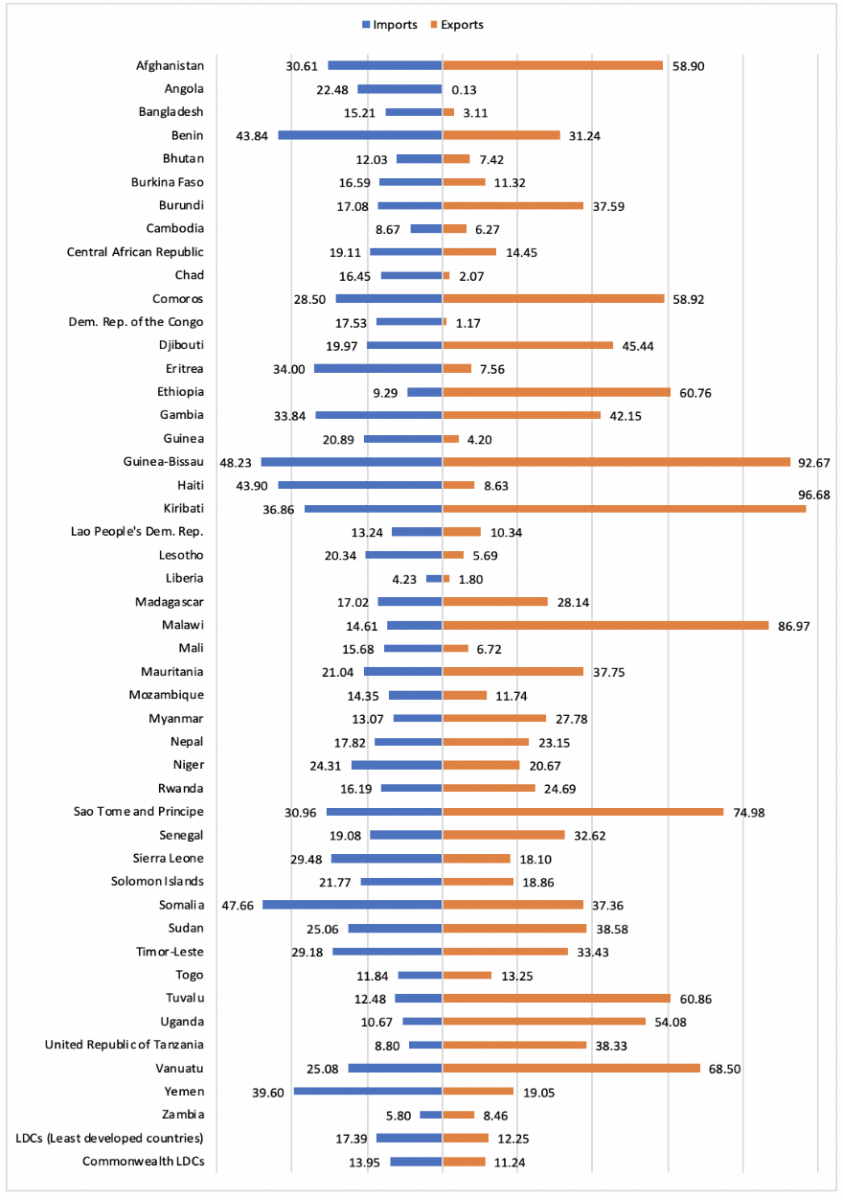

The share of food in LDC imports is more than double the world average. In 2018, global food trade was worth US$1.5 trillion – or around 8% of merchandise trade – compared to 17% (or US$46 billion) of LDC merchandise imports. For the 14 Commonwealth LDCs, food was 14% (or US$14 billion) of their merchandise imports (see Figure 2). Overall, Bangladesh was the leading importer in absolute terms (US$7 billion). However, in relative terms, the largest importers were Kiribati (36%), The Gambia (34%) and Sierra Leone (30%) (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Share of food in LDC merchandise trade (%, 2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

The share of food in LDC merchandise exports is also above the world average (14% vs 8%, respectively), except for Bangladesh (see Figure 4). In 2018, the value of total food exports of LDCs was around US$7 billion. Uganda was the leading exporter in absolute terms (US$1.7 billion), whereas Malawi (87%), Uganda (54%) and Tanzania (38%) had the highest relative share of food in their exports.

The Pacific LDCs have the largest share of food in their merchandise trade, both for exports and imports, at about 24%. Most of their exports are fish products to richer markets, whereas food imports are more diverse, most likely because of the physical constraints to land-based agriculture in small island developing states.

Figure 3: Share of food in merchandise trade for Commonwealth LDCs (%, 2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

Leading food suppliers to LDCs

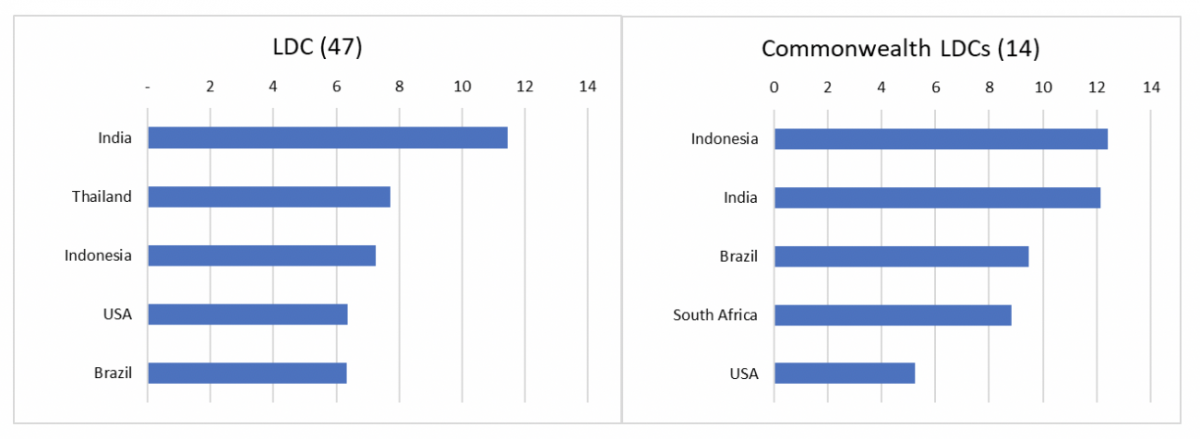

Excluding the USA, the top four suppliers of food products to LDCs are developing countries. India is the largest source of food imports for all LDCs, accounting for about 12% of their food imports (see Figure 4). South Africa is the leading supplier to African LDCs, accounting for 18% of their imports, and Australia is the leading supplier to the Pacific LDCs. The other two big food suppliers to LDCs are Brazil and Thailand.

Figure 4: Top 5 suppliers of food products to LDCs

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

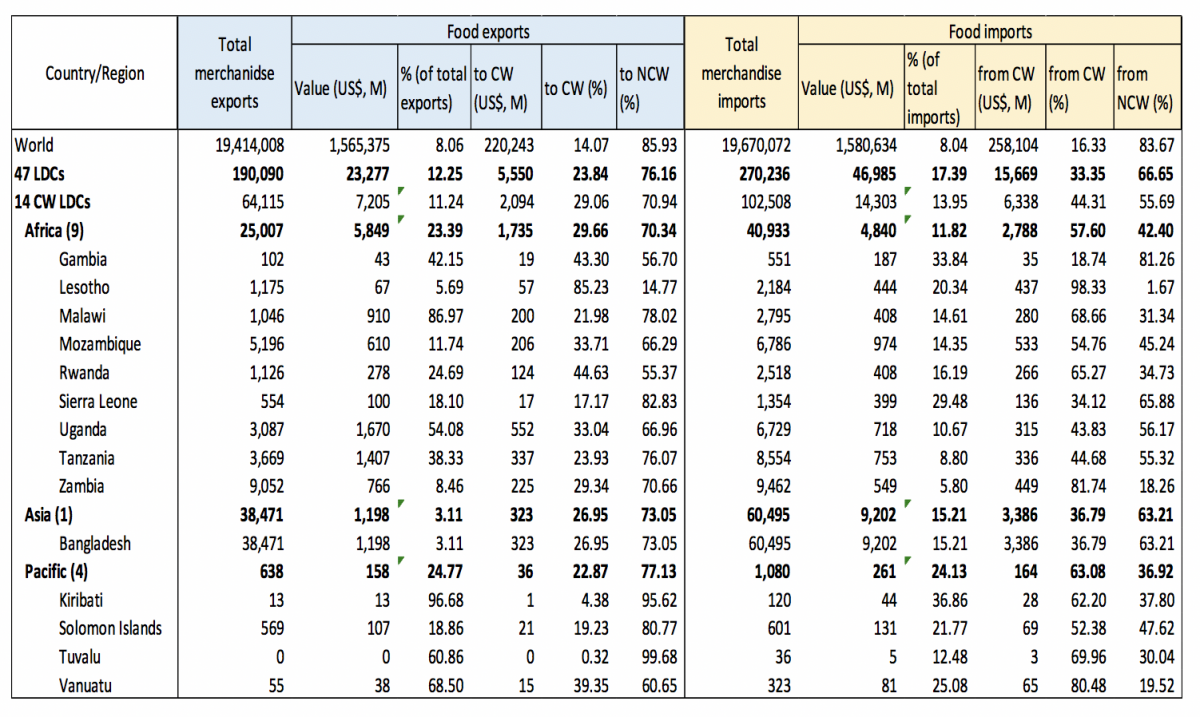

As expected, there is large intra-Commonwealth trade in food products for most LDCs, especially in Southern Africa and the Pacific, reflecting the salience of regional production and supply chains and the Commonwealth trade cost advantage. Commonwealth LDCs source around 45% of their food supplies from other Commonwealth countries (see Table 1). The average for the nine African LDCs is around 57% and 63% for the four Pacific LDCs. The share of intra-Commonwealth food trade is above 60% for 7 LDCs: Lesotho (98%), Malawi (68%), Rwanda (65%), Zambia (81%), Kiribati (62%), Tuvalu (70%) and Vanuatu (80%).

Table 1: Intra-Commonwealth trade in food supplies (2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

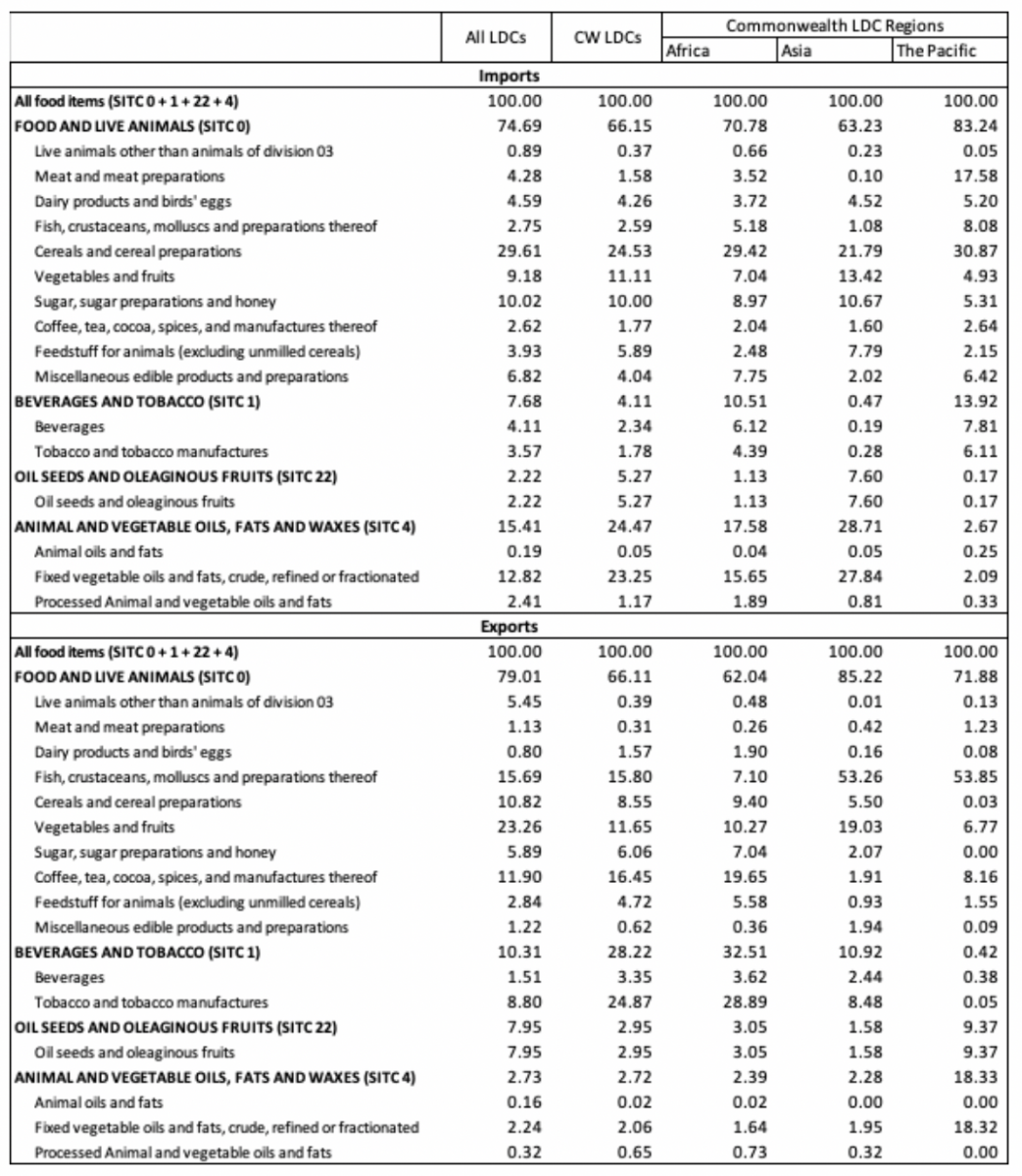

Composition of food trade

LDCs import a range of food items, including basic staple food items such as cereals, fish, dairy products and edible oils (see Table 2). The share of staple food items in total food trade is around 70%. Cereals are an essential part of people’s diets, a core nutritional need in places where there is high food insecurity. The share of cereals in food products varies from 20% for Bangladesh to 30% for the Pacific LDCs.

Edible oil is the second largest import item, with its share ranging from 12-16%. Bangladesh is the largest importer of edible oil, which represents around a third of its total food imports. By comparison, the food exports of LDCs are quite different: fruits, vegetables, fish and beverages are large export items.

This pattern of food trade in LDCs indicates that they will be affected differently depending on their existing economic vulnerabilities and position in the food supply chain (see Figure 5). COVID-19 has already affected the production and supplies of essential food items such as rice, wheat and maize in domestic and international markets. Disruption in logistics, lockdowns and economic recessions have led to supply shortages in several countries.

This is in addition to a steep decline in remittances and tourism receipts and the fall in commodity prices. All these factors have adversely impacted LDCs’ access to basic food supplies. Some LDCs are experiencing humanitarian crises [2], and are likely to be adversely affected in terms of the availability of adequate basic food supplies.

Figure 5: Share of food in LDCs merchandise trade (%, 2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

Table 2: Composition of LDC food trade (%, 2018)

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using data from WITS)

Way forward

Overall, global food markets appear to have functioned relatively well given the severity of the COVID-19 disruptions. However, the pandemic could exacerbate the situation in specific locations/countries that were already under pressure, especially LDCs.

With the coronavirus spreading in developing countries, including in some major suppliers of food like Brazil, India and South Africa, LDCs must consider adopting trade policy measures that enable them to import food from alternative sources. In this regard, LDCs can take advantage of regional cooperation initiatives to help mobilise resources to ensure access to and availability of food during the pandemic as well as develop strong regional supply chains to mitigate future crisis food requirements.

For example, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) organ on Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources has adopted initiatives to assess the impact of COVID-19 on food security in the region, identify structural constraints and provide information and recommendations to strengthen regional capacities for emergency response to ensure adequate food supplies in the region. Elsewhere, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has developed a COVID-19 Agri-food Risk Management Framework to guide planning and risk management at the regional level.

In addition, LDCs must explore various ways such as maintaining physical distance, reducing interaction among co-workers and providing sufficient hygiene products to ensure health and safety, aimed at minimising disruption to domestic food production. Unless addressed adequately and swiftly, the long-term effect of a hunger pandemic could imperil the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 2 on improving food security and ending hunger.

-------------------

[1] The remaining nine net food exporting LDCs are Myanmar, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, Ethiopia, Zambia, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar and Mauritania.

[2] Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Tonga suffered significant damage and a humanitarian emergency following Cyclone Harold in April 2020. Bangladesh faces the challenges of feeding the Rohingyas and recovery from recent Cyclone Amphan in the Bay of Bengal.

Header image ©EIF, in text images ©EIF NIU Mali.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.